We all know what it looks like when book banners come for your school district, right? Angry parents reading salacious passages from certain books at school board meetings, yelling and screaming at trustees to remove a handful of books?

That still happens, but it’s time to update your image of how book banners operate. In 2025, they are much more efficient, relying on behind-the-scenes pressure and much larger lists of books.

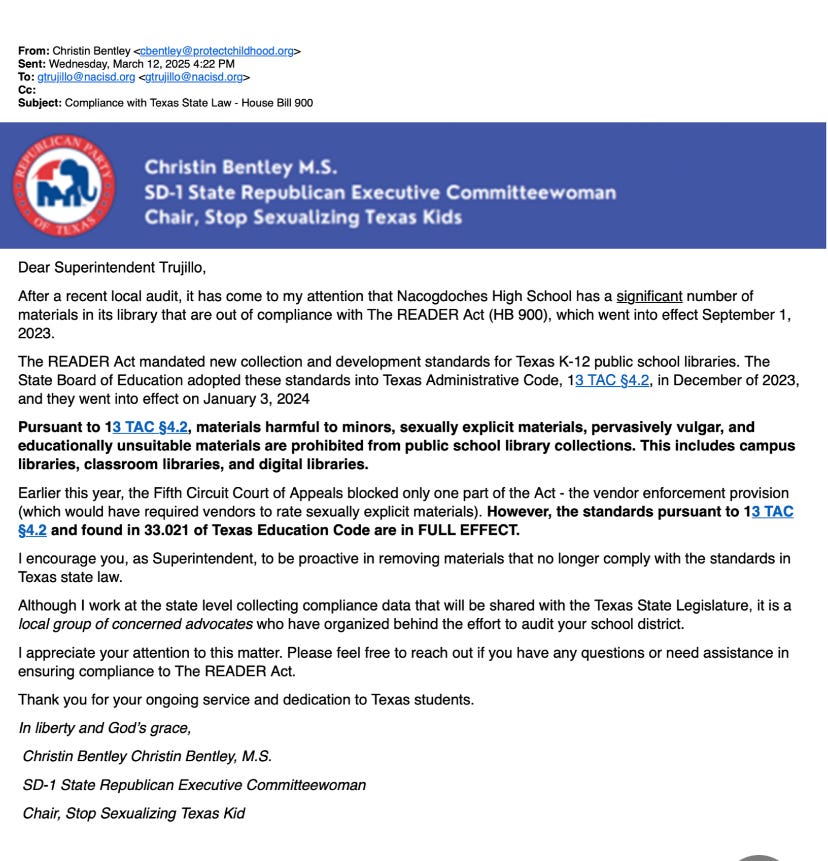

I’ve written about Citizens Defending Freedom’s email campaigns before, but new documents from Nacogdoches ISD in Texas also provide an excellent case study in how book removals work today. As I explain in the video above, a Republican Party official sent the following email to the district’s superintendent, demanding the removal of 140 books from school libraries1:

There are some positives in this story: First, parents and students in the district are standing up in response—look for more information soon from Texas Freedom to Read Project about their efforts.2 And although the district has pulled the books from general circulation and restricted student access to those with parental permission, they are promising to “vet” the books before making final decisions. That’s good news, if the vetting process is transparent and involves thoughtful consideration of the works as a whole. When books are reviewed in their entirety, they are overwhelmingly returned to library shelves.

But something else I want to emphasize: Book banners have been swearing up and down that they’re not going after classic works of literature. During last week’s floor debate on SB13, the bill’s House sponsor, Representative Brad Buckley, called the idea a “red herring.”

Among the books targeted in Nacogdoches are Richard Wright’s Native Son, Maya Angelou’s I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five, and Toni Morrison’s Beloved and The Bluest Eye. The list includes Nobel Prize winners, Pulitzer Prize winners, National Book Award winners and finalists, and several books named by the Modern Library as among the top 100 novels of all time. Thirteen of the books on the list have appeared on the AP Literature exam, most of them multiple times.

So when Texas book banners say they’re not trying to remove classic literature from schools, they are lying.

That said, I want to make sure we all understand that great literature didn’t stop being written in 1950, or 1970, or 1985. Our students’ loss of great contemporary literature is a tragedy too.

Correction 6/3/25: In the video I said the list was 146 titles.

Gotta love the student who referred to the deceitful GOP official who sent this email as a “shadowy figure.” At a board meeting, that student asked, “Why is the district acting on the orders of a shadowy figure who seems to come above the people that actually live here?” Great question!