Jared Patterson’s HB 900, named the READER (Restricting Explicit and Adult-Designated Educational Resources) Act is ostensibly about libraries, not instruction in the English classroom.

Ostensibly.

The bill requires vendors that sell books to schools to label any books that fall under two newly defined categories: “sexually explicit” or “sexually relevant.”

In the bill, sexually explicit material “describes or portrays sexual conduct, as defined by Section 43.25, Penal Code, in a patently offensive way” according to community standards. Last week, Patterson clarified that would likely include books that describe or portray prostitution—like Lonesome Dove. It would also likely include books that describe rape or incest, like The Bluest Eye, which has been removed from several Texas districts, and which was specifically mentioned (with relish) by multiple commenters as a sexually explicit book in testimony on the bill. These books would be banned from all Texas schools under the bill. Vendors couldn’t sell them to districts, and districts couldn’t buy them.

“Sexually relevant” books would be those that describe or portray sexual conduct, but not in a way that is “patently offensive” to community standards.1 Accessing these books would require parental permission; in the hearing, Patterson said he envisions them being kept in a separate section in the library, one that only students with that permission could enter.

Attention surrounding the bill has rightly focused on what it would mean for school libraries, but as an English teacher I want to ask committee members what it would mean for classroom instruction, and share my concern that the bill could hobble the teaching of literature in Texas high schools. To visualize how, look at the two images below.

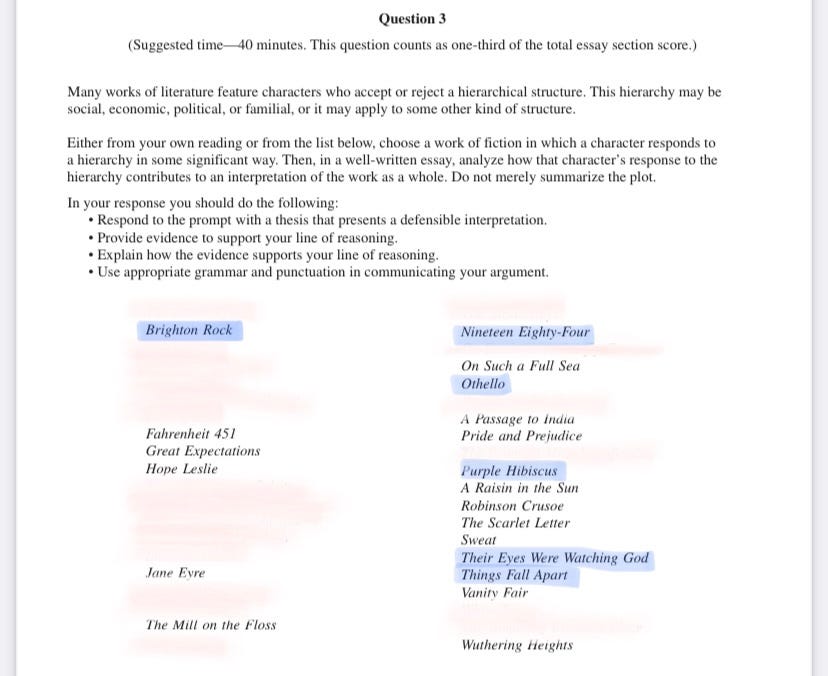

Figure A is Free-Response Question 3 from last year’s Advanced Placement Literature exam.2 The AP Literature test is taken by hundreds of thousands of high school students each year who hope to earn college credit with their score. Tens of thousands of Texans took it last year.

The format of Question 3 is always the same: it names a common theme in literature and then asks students to select and interpret one work of fiction in which that theme appears. It’s meant to test not only their analytical skills, but also their general literary knowledge, since the more novels a student knows that feature the given the theme, the more likely it is that they’ll have something of substance to write. To help students out, the College Board provides a list of 30 - 40 novels; students may write about one of the novels on the list or any other they’ve read in class or independently.

To be clear, this is not a curriculum or a required reading list. But it is an indication of the kind of novels the College Board and, by extension, college literature professors, expect American students to have read by the time they’ve finished high school. Importantly, it’s also a tool, both for students taking the test and for teachers planning their course.

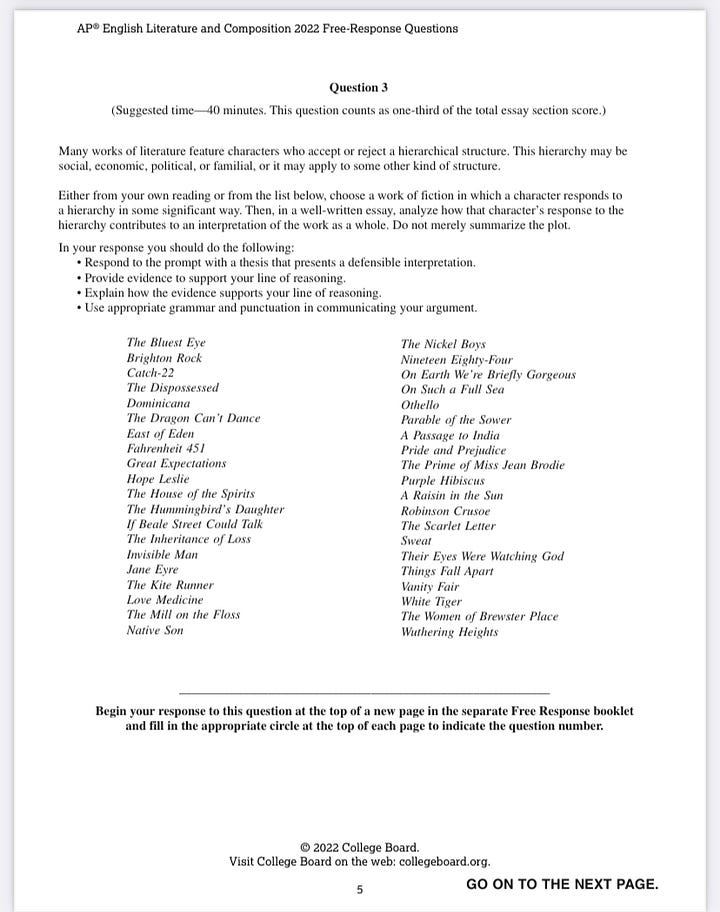

You’ve probably already gleaned the problem: the very first book on the list is The Bluest Eye, one of the books most frequently targeted for restriction or removal over the past two years.3 But that’s just the start. In Figure B, I’ve whited-out every text that would likely fall under Patterson’s “sexually explicit” category, and thus be banned from all school libraries in the state.4 I’ve also highlighted in blue the books would likely be labeled “sexually relevant,” and thus require parental permission to access.5

Now, there is a clause in HB 900 that says that the definition “sexually explicit” excludes “library material directly related to required curriculum, as referenced in Section 28.002.” But as Representative James Talarico pointed out in last week’s hearing, Texas doesn’t have a fixed statewide English curriculum beyond a general requirement that schools teach English language arts. We certainly have no state reading list. Instead, districts, schools and sometimes teachers have traditionally had leeway to order and assign books to meet the TEKs (the knowledge and skills designated essential by the State Board of Education). So what books does that clause protect?

It’s hard to imagine school leaders feeling comfortable ordering books like The House of the Spirits or The Kite Runner that might be designated “sexually explicit” by vendors. Similarly, it’s hard to imagine activists now angry that The Bluest Eye sits on a library shelf would be okay with kids bringing it home as required reading.

That’s a problem. I’m concerned that, if HB 900 passes, Texas students won’t receive the quality of literary education available to students elsewhere. To visualize how big a problem this is, imagine yourself as a high school student sitting down to take the AP Literature exam and receiving the book list in Figure B, rather than the one in Figure A.

Or imagine yourself as an AP English teacher trying to put together a course syllabus using only the books on list B as guidance, rather than those on list A.

I am not suggesting that the AP system is the be-all-end-all measure of a good literary education. But the College Board is correct that these books “provide rich opportunities for students to develop an appreciation of ways literature reflects and comments on a range of experiences, institutions, and social structures.” These are good books—in every sense of the word.

And the fact that these books contain mature material shouldn’t frighten parents or community members. Students taking the AP Literature exam are generally 16-18 years old. Many work and pay taxes; many vote. Some are parents themselves. We want them to think about the questions these texts raise—questions like: Why do people hurt children?, and What do we do in the face of that reality? Indeed, we have expected students their age to wrestle with questions like this for generations. In fact, Toni Morrison first appeared on the AP Literature exam in 1981, two years before Representative Patterson was born. The Bluest Eye first appeared on the exam in 1995, before Patterson entered high school.

So it’s clear that HB 900 doesn’t solve any real problem that high school students or teachers face. But I do worry that it would make teaching and learning in Texas much more difficult. I hope that committee members will consider the burdens it will place on Texas educators and students, and the limits it will place on student learning.

An example of “sexually relevant” but not “sexually explicit” might be the pear tree scene in Their Eyes Were Watching God, which is drenched in sexuality and clearly about masturbation by a teenager, but figurative enough that drowsy tenth-graders often overlook the symbolism.

You can view AP Literature FRQs from multiple years at this link. As in 2022, most years the AP exam includes books that would be considered “sexually explicit” under HB 900, such as The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, Atonement, Beloved, or Lolita. It’s also worth noting that Question 1 and Question 2 from previous years also often feature passages and poems from books that could be banned from schools under the measure.

Novels by Toni Morrison, the author of The Bluest Eye, have appeared on the AP Literature list more than 30 times. The Bluest Eye itself has been listed on the test 5 times.

So no one thinks I’m exaggerating that these works would qualify as “sexually explicit,” I’m linking below a sample of passages from whited-out texts that would likely earn them that label, according to HB 900’s definitions and Rep. Patterson’s clarifications in last week’s public hearings. I haven’t had time to screenshot passages from all of the books I’ve whited out, but I’ll update as my work allows.

An additional factor worth considering is that teachers in Texas are likely reluctant to assign other books that remain on the list, including Raisin in the Sun and On Such a Full Sea, as they risk drawing complaints related to SB3 from the 87th Legislature.