Toni Morrison did it.

Last July, I was one of about a hundred Texans signed up to testify at the state Capitol in front of the House Committee on Public Education about school book bans and “parental rights” and, as public comment started, I didn’t know what I was going to say. It’s not that I was unprepared: I knew the points I wanted to make, and I had a written draft ready. I just didn’t feel like my testimony was really together that morning or that afternoon, and I kept tinkering with it while I watched the proceedings already underway.

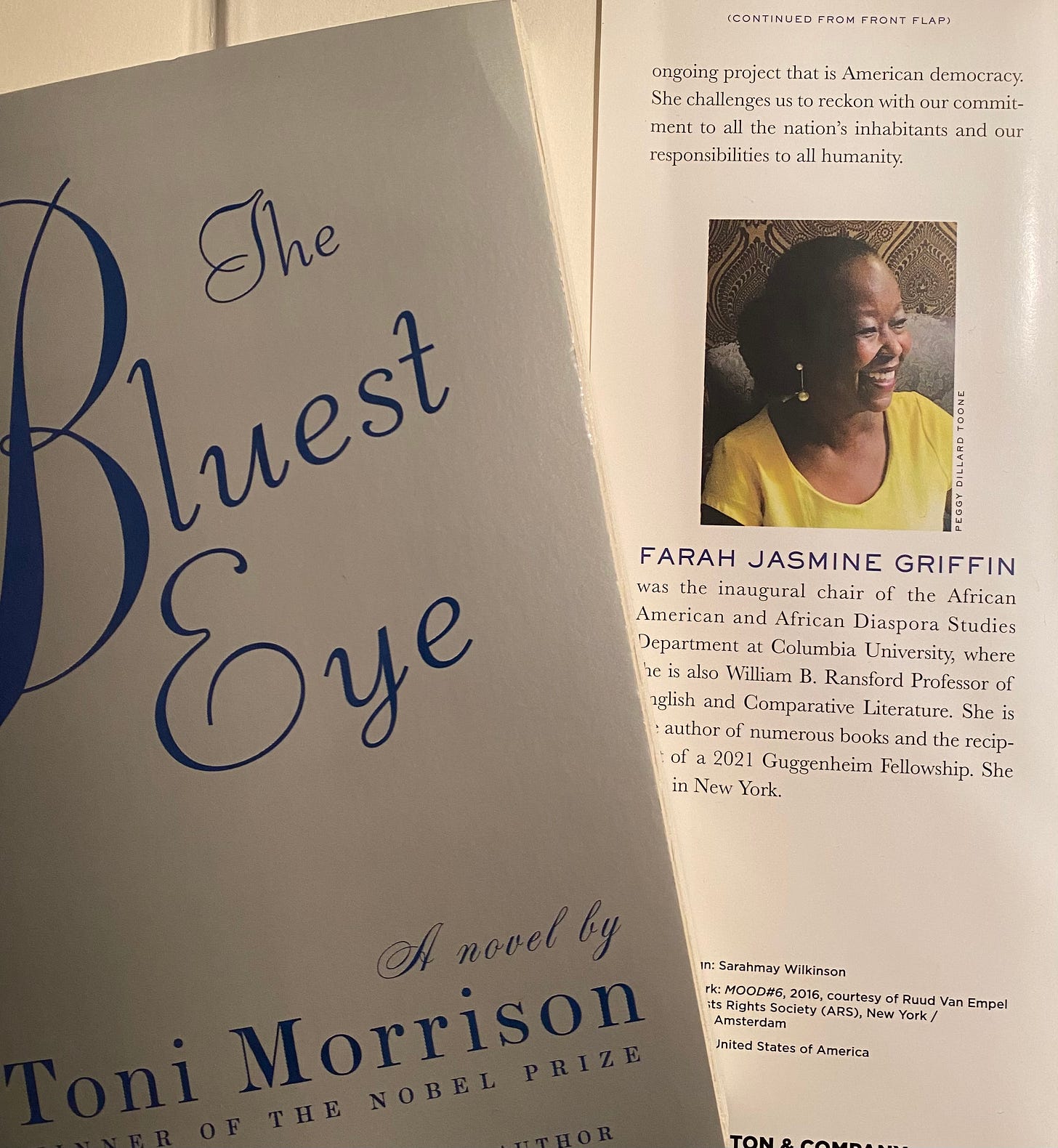

Then, as testimony continued into the evening, one of the commenters who signed up to speak before me read a passage from The Bluest Eye. I knew who this commenter was—she’s a leader of the Gillespie County chapter of Moms for Liberty and a founder of a group called Make Schools Safe Again. Not only was she instrumental in challenging dozens of books at schools in her Hill Country town of Fredericksburg, she’s also been appearing on podcasts and joining Facebook groups of like-minded activists around the state, giving them advice on how to take books away from students in their communities.

If you’ve followed book-banning news over the past two years you know exactly which passage she read: the description, about 200 pages into the book, of Pecola’s rape by her father, Cholly. It’s a brutal scene, and pro-censorship activists take lurid pleasure in reading it aloud at school board meetings and then noting trustees’ reactions. Their performances made The Bluest Eye one of the five most-challenged books of 2022.

“This book violates the Texas Penal Code and legally should not be distributed to children,” she said.1

And: “I ask if any of you could tell me the literary or educational value that my child gets from reading this book.”

It was, for me, a moment of anger and clarity. My testimony came to me in a flash: I would answer that question. I would talk about Toni Morrison. I would put her in context with other great writers—Faulkner, Joyce, Steinbeck—whose books also contain scenes that, read aloud, would make an audience of legislators grimace. I would talk about the recognition her books have received, how she’s arguably the most acclaimed American novelist of the past 60 years. I would point out that The Bluest Eye first appeared on the AP Literature Exam, which tens of thousands of Texas high school students take each year, in 1995, when I was still in high school. I would talk about my daughter, and how I want her to have access at school to all of the best writing, and to have teachers who push her to read about important topics, even when they make her uncomfortable.

But I only had three minutes.

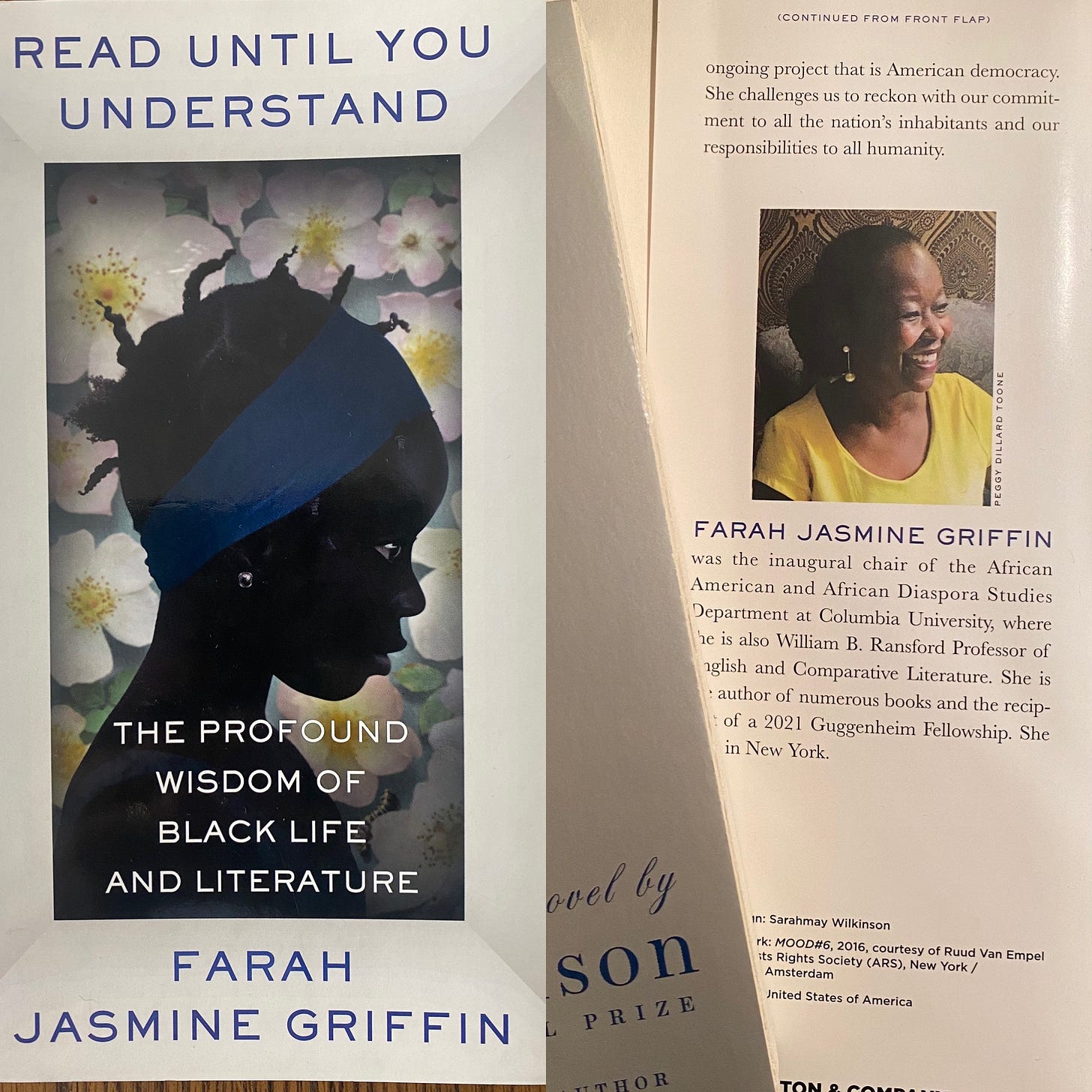

A much better and more comprehensive answer to that question can be found in Farah Jasmine Griffin’s extraordinary book Read Until You Understand: The Profound Wisdom of Black Life and Literature. Griffin, a professor of English, Comparative Literature, and African American and African Diaspora Studies at Columbia University, is a wide-ranging scholar whose previous work includes studies on jazz, on the African-American migration narrative, on Black female artists during World War II. But Read Until You Understand is a more comprehensive project than any of her previous books; it was born from classes on African-American Literature she has taught undergraduates for decades at Columbia. I’ve written before that I wish someone had pushed Toni Morrison’s writing into my hands when I was a high school student. I wish just as fervently someone would push Read Until You Understand into the hands of the legislators, school board trustees, teachers and administrators and parents who make decisions about our children’s education.

I can’t believe we have to ask these questions, but apparently we do: What is the value of reading Toni Morrison? For that matter, what is the value of reading Black literature in general? The questions are hard to separate, because the things that get Morrison’s books challenged show up throughout Black literature: trauma, including sexual trauma; the effects of systemic racism; the brutality of marginalization and poverty. That’s why so many acclaimed Black writers can be found right alongside Morrison on district book challenge lists: Jesmyn Ward, Ta-Nehisi Coates, Alice Walker, Richard Wright, Kiese Laymon, James Baldwin. On top of that, Morrison was both an influential writer and an exceptionally intertextual one—one whose work is intimately connected to other writers in both the Black canon and American literature as a whole. Even the passage that Mom for Liberty read that day at the Capitol echoes a similar rape scene in Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man. In a real sense, to attack Toni Morrison is to attack Black literature.

So it’s no surprise that Morrison plays an outsized role in Read Until You Understand. Griffin started what she calls a “lifelong intellectual, aesthetic, political, and spiritual engagement” with Morrison’s work when she was 13, and Morrison’s novels feature in almost every chapter of Griffin’s book.

But Read Until You Understand isn’t just about Morrison. Griffin sets a big task for herself, writing that her goal is to explore how books by African American authors “speak to ideas and values that have concerned humanity since the beginning of time.” Among these fundamental questions, Griffin focuses on two: First, “What might an engagement with literature written by Black Americans teach us about the United States and its quest for democracy?” Second, “What might it teach us about the fullest blossoming of our own humanity?”

Read Until You Understand serves as a sort of syllabus for approaching those questions. It’s broken into ten chapters, each addressing one aspect of either American democracy or what the Catholics call “human anthropology.” The authors she poses her questions to range from Phillis Wheatley to James Baldwin, from Frederick Douglass to Toni Cade Bambara. As any professor would, Griffin puts texts in conversation with each other, revealing the fractious nature of the body of Black American literature while still making the case that that body presents a distinct ethic and “demonstrates how a people have lived with style, grace, brilliance, and beauty in the face of persistent crisis and catastrophe.”

If this were all Griffin did in Read Until You Understand, the book would be a valuable contribution to the moment, a treasure at a time when Black literature is under fire. But Read Until You Understand is so many other things. Among them, it’s a memoir in books: Griffin describes reading as the way she has always made sense of her relationship with her family and the community that surrounded her. And, since her life experiences have included many of those moments of crisis and catastrophe—her father’s fatal mistreatment by Philadelphia police, the early deaths of many men in her orbit—reading Black authors has always been for her both political and intensely personal.

Griffin describes the informal but rigorous course of study her father gave her when she was a child—the country’s founding documents, but also “Toussaint Louverture, Nat Turner, Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, the Black Panther Party, and Angela Davis.” She writes, “Because I adored my father and cherished being with him, I experienced learning as love.” And that love deepened and broadened as she encountered masterful novels, music, and art made by Black creators.

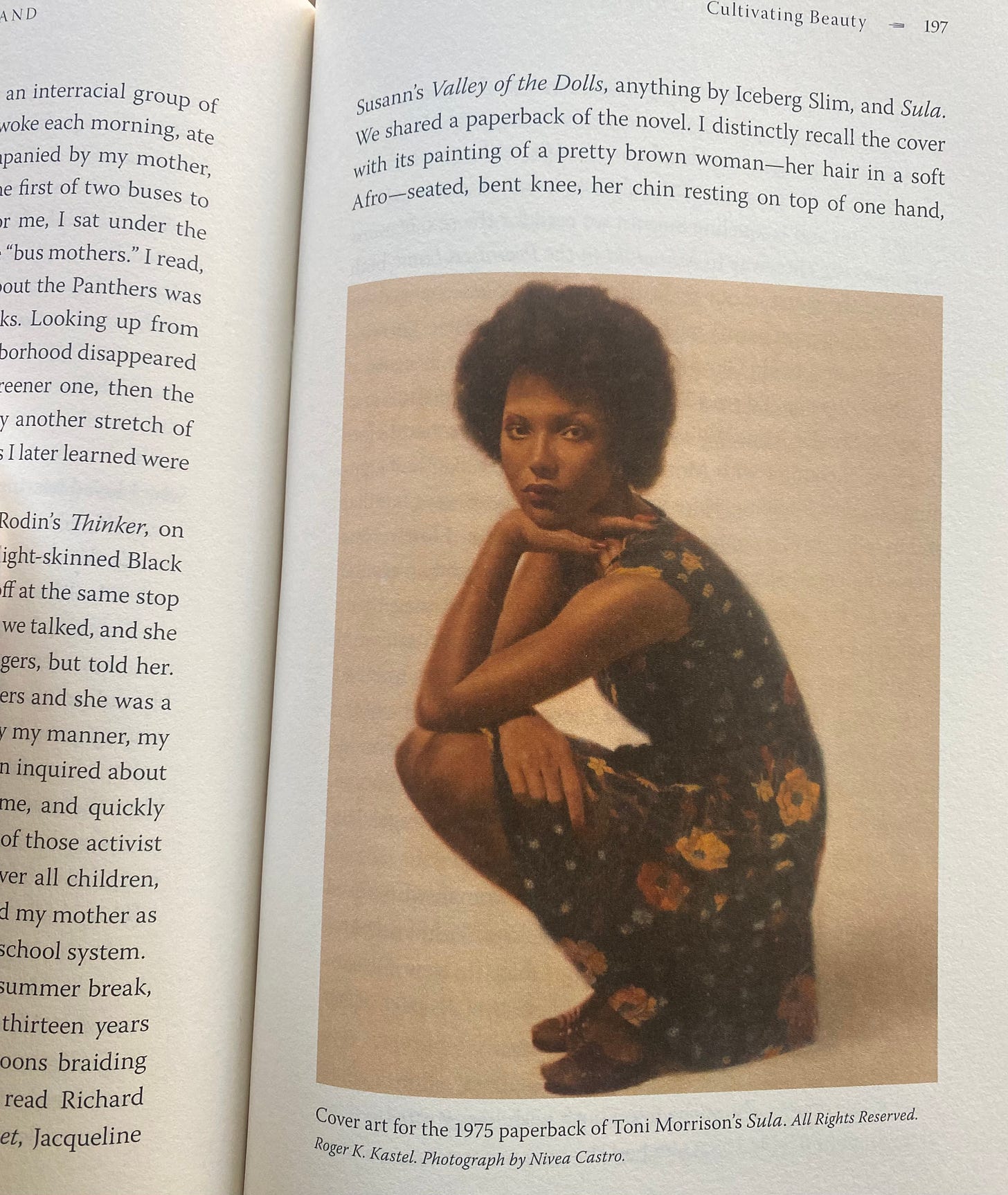

Griffin describes encountering Morrison the summer she was 13 (Think of the prefrontal cortex, the Moms for Liberty gasp!), when she and her friends passed around a paperback copy of Sula between jump-rope sessions. “Here was a world in some ways familiar and in other ways completely different from the one I knew,” she writes. “Here was a language that sounded like the language the women around me spoke, but presented in a way so that I heard its imagery, its beauty, its rhythm.”

And: “When I first encountered this book as a teenager, I took tremendous pleasure in reading the language aloud, in thinking about the characters when I was away from them; and upon finishing it, I wondered, why did I now see my world, my family, my neighbors differently? Why did it seem so overwhelmingly beautiful, and why did it seem to stretch my own understanding of what ‘beauty’ is or means?”

Why did it seem to stretch my own understanding of what ‘beauty’ is or means? This is what every English teacher dreams of when assigning a text. Besides that, it’s beautifully expressed. “I cannot write about Black women and Black women’s texts in a language that I find ugly,” writes Griffin elsewhere. It shows. More than a syllabus and memoir, Read Until You Understand is also a garden: a source and container of beauty, and something beautiful in itself.

“Why are there people in the world that so passionately want to hurt children?”

That’s another question the Mom for Liberty asked at the Texas Capitol. It’s a question lots of high school students confront, too. Maybe they’ve been hurt. Maybe they know someone who has been hurt. Maybe the question comes when they’re learning about historical atrocities—the Holocaust, for example, or the Indian Removal Act. Maybe it comes when they learn (if they learn) about the breakup of Black families during slavery, or about family separation at the southern border.

If that Mom for Liberty had thought for just a bit longer, she might have realized that that question points to an answer to her other question, the one about the value of reading Toni Morrison. We read a book like The Bluest Eye to think about questions like that, or its corollary: how do we live in a world where people hurt children?

“When the community goes against its own ethic of caring for those who are put outdoors, the most vulnerable are destroyed, betraying the community’s capacity for cruelty.” That’s the lesson Griffin distills from The Bluest Eye. She continues: “The Bluest Eye offers a critique of Black people’s exclusion from America, but more importantly, it asks, ‘How do we treat each other? Do we mirror and echo the values of the larger society or do we live by an alternative set of values?”

And, as Griffin outlines, Morrison presents the consequences of each alternative. Yes, we witness Pecola’s destruction. But Morrison also shows that alternative set of values in the family life of the book’s narrator, Claudia MacTeer—and that is the vein of the story that holds Griffin’s attention. She zooms in on one of Morrison’s gorgeous similes:

Love, thick and dark as Alaga syrup, eased up into that cracked window. I could smell it—taste it—sweet, musty, with an edge of wintergreen in its base—everywhere in that house.

With this description of Claudia’s mother’s care for her sick children, Griffin tells us, love “is neither abstract nor romantic. It is embodied in action, in forms of maternal care.” And, Griffin explains, “the young girls who are recipients of this kind of care, especially during times of illness, freely give it to others in need.”

Crucially, Read Until You Understand is not a book about suffering, or trauma, or despair; it’s a book about what Black literature tells us we can do in the face of those things, how we can cultivate mercy, justice, beauty, love, and joy. The book’s ethic seems to echo Christina Sharpe’s essay “Beauty is a Method”:

I learned to see in my mother’s house. I learned how not to see in my mother’s house. How to limit my sight to the things that could be controlled. I learned to see in discrete angles, planes, plots. If the ceiling was falling down and you couldn’t do anything about it, what you could do was grow and arrange peonies and tulips and zinnias; cut forsythia and mock orange to bring inside.

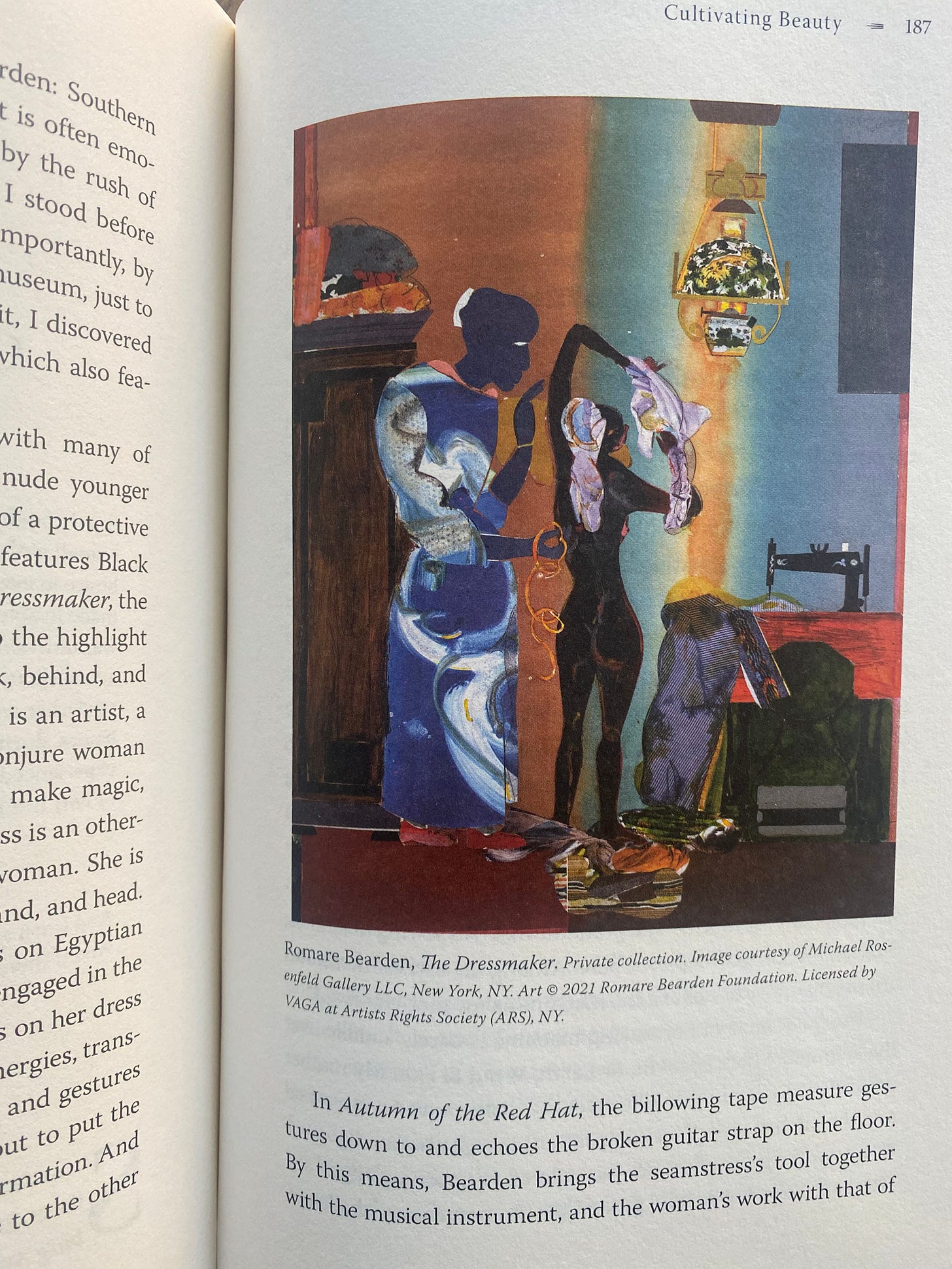

Griffin offers her close reading of The Bluest Eye in the first chapter of Read Until You Understand, in a section entitled “Legacy, Love, Learning”—the three things her family bequeathed her. The book culminates with two chapters about beauty, “Cultivating Beauty” and “Of Gardens and Grace.” Morrison is the through-line, the exemplar and guide for the ethic of beauty Griffin says characterizes Black Americans cultivate in the face of injustice and cruelty.

But I’ve been dancing around the specific way that Mom for Liberty phrased her complaint about Morrison. Because she didn’t ask, exactly, what is the value of reading The Bluest Eye. To be perfectly precise, this white mother asked: what is “the literary or educational value that my child gets from reading this book”?

Looking back over the quotes I’ve pulled, I’m not sure how persuasive they would be to that Mom for Liberty. Why would she care that Griffin found in Morrison “the language the women around me spoke”? What does that mean to her child?

Morrison famously refused to cater her writing to white audiences. But that never meant that her work wasn’t valuable to white readers. Griffin mostly follows Morrison’s lead: Read Until You Understand isn’t an apologia or an explanation of Black literature for white readers. But the book—the syllabus, the memoir, the garden—is a comprehensive, complicated, and compelling argument for those with ears to hear about the contribution Black writers have made to the world of letters. “I hope my words will entice you pick up these works and read them,” Griffin writes. “To do so will only enrich your experience, understanding, and life.” The same can be said for Read Until You Understand.

It should go without saying, but this is false. The Bluest Eye was published in 1970, and in 53 years, no one in the US has ever been prosecuted for selling it, lending it, or giving it to a minor. The idea is absurd.