Six Anti-Book Bills I'm Watching in the Next Texas Legislative Session (besides HB183)

It's already started, y'all. We need to get working.

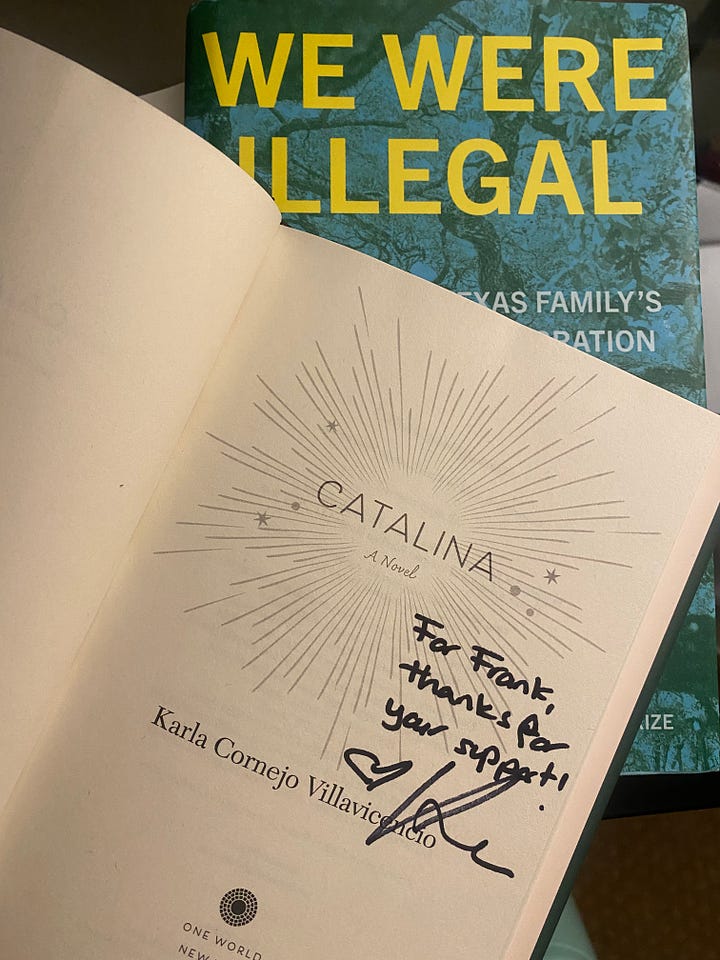

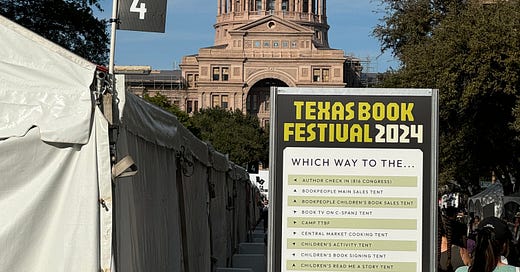

I’m going to start with something cheerful: On November 16 and 17, Texas Freedom to Read Project participated as an exhibitor at the Texas Book Festival, an annual Austin event that takes place in the Texas Capitol and in tents along Congress Avenue. It was great for us: We met with friends from Authors Against Book Bans, Texas Freedom Network, Mothers for Democracy, and Texas Blue Action. I saw old teaching and grad school colleagues and former students. I met author Karla Cornejo Villavencio and had her sign my copy of her new novel Catalina. Most of all, we talked to thousands of people who care about books—so many people walked by in “Read Banned Books” shirts and wanted to hear how they can help fight for the freedom to read and oppose book bans in public schools and libraries.

But as lovely as the event was, it was hard to ignore the shadow cast over it by the giant pink granite building at the end of the street.

A few days before the festival, pre-filing of bills for the 2025 legislative session began, and lawmakers immediately unleashed a flurry of proposed laws they had been dreaming up for months.

You will not be surprised to learn that the offerings so far are nightmarish. In addition to a proposed monument to aborted children, a bill banning undocumented children from state public schools, and a bunch of laws aimed at making the lives of trans people miserable and precarious, day one of pre-filing treated us with several attempts to further restrict reading rights for Texans.

The headliner of those bills is House Bill 183. It was filed by Jared Patterson, the author of last session’s HB 900 (the so-called READER Act), which has already done immense damage to Texas schools.1 This year’s bill would enable the State Board of Education to review and remove books from all public schools in the state, essentially creating a statewide banned books list, something we’re already seeing in Utah and South Carolina. HB 183 got a boost this week when the State Board explicitly asked the legislature to give it the authority to rate and remove books, so it seems like this will be the big battle over books in 2025’s session.2

But it won’t be the only one! Below are six more anti-book bills you should watch out for—and publicize, and speak out against, and fight—in the new year.

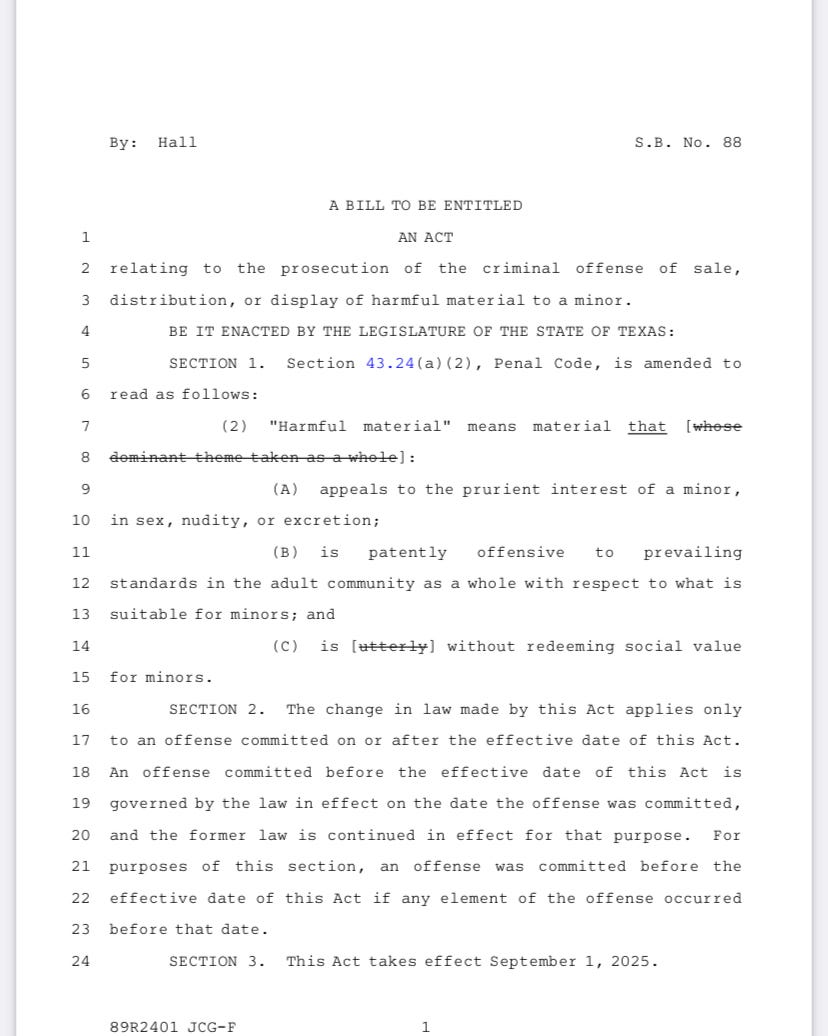

Senate Bill 88 (Bob Hall)

What does it do?

Texas law, reasonably, forbids distributing material defined as “harmful to minors” to anyone under 18. Like most states, Texas currently defines “harmful to minors” as material whose “dominant theme taken as a whole”:

(A) appeals to the prurient interest of a minor, in sex, nudity, or excretion;

(B) is patently offensive to prevailing standards in the adult community as a whole with respect to what is suitable for minors; and

(C) is utterly without redeeming social value for minors.

That’s also reasonable, and is based on a modified version of the “Miller Test,” the Supreme Court’s formulation for determining whether or not a book, film, or other material is obscene and thus not protected by the First Amendment. The Miller Test is a cornerstone of First Amendment jurisprudence and is the reason you can’t be arrested for possessing, selling, or lending books like I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings or Salvage the Bones.

Bob Hall’s Senate Bill 88 would remove the phrase “dominant theme taken as a whole” from the definition of “harmful to minors.”3 In other words, a book with one sex scene or scene of sexual assault could be ruled “harmful to minors,” no matter the intent of the scene, the context surrounding it, or the value of the book as a whole.

This is a longstanding goal of Texas book-banners, who have been stymied in their attempts to criminalize literature by the fact that, by law, a well-written, culturally valuable novel that contains a realistic or artistic depiction of sex is not pornography. Judy Blume’s Forever is not pornography; neither is Beloved or Ulysses.

Republicans introduced a similar measure in the last legislative session; it died in committee.

Why is it bad?

Phew, boy. Messing with the foundation of our current understanding of the 1st Amendment is, to put it mildly, not a good idea.

The consequences of removing the “as a whole” clause from the definition of “harmful to minors” go far beyond school libraries. If material is “harmful to minors,” it is illegal for anyone to provide to anyone under 18. That means public libraries couldn’t lend them, and bookstores couldn’t sell them.

And remember, the people pushing this bill think Scholastic Book Fairs sell “pornographic” material.

If this bill passes, we’re talking about a world where bouncers check IDs at the entrance of Barnes & Noble. Where the Texas Book Festival would have to make sure that no one under 18 could sneak in to hear Cristina Rivera Garza or Colson Whitehead read from their books.

And that’s not all. Apart from the awfulness of this bill in itself, it would amplify the dangers of other bills, like …

Senate Bills 89 & 242, House Bills 267, 947, 995 (various authors)

What do they do?

Current Texas law says it is an “affirmative defense” against allegations of distributing harmful materials for minors if you do it for a legitimate educational reason. These copycat bills all remove that affirmative defense for educators.

That said, these bills won’t actually do much unless SB 88 or a bill like it also passes. Librarians aren’t actually stocking materials that are legally obscene or harmful to minors under current law. So the “affirmative defense” is really redundant.

But if the definition of “harmful to minors” changes to include Toni Morrison or Alice Walker books, all bets are off.

That doesn’t mean these bills are nothing to worry about if SB 88 doesn’t pass. As we’ve seen with the so-called READER Act, the effects of a law can go far beyond its actual dictates. The law would likely be used as one more tool to frighten librarians and contribute to the chilling effect that is already decimating libraries around the state.

Still, part of me thinks of these bills as traps. I worry that the people behind them know they won’t actually do anything and, besides giving those people a chance to run down schools and librarians, their actual goal is to get anti-censorship folks on the record saying that educators need the right to give kids harmful material.

The people behind the book-banning movement are cynical showboaters who seek to discredit their perceived political opponents rather than engaging our arguments in good faith. Our messaging on these bills needs to be disciplined and well-thought-out.

House Bill 1025 (Matt Shaheen)

What does it do?

This bill would create an “Inspector General” for Texas public schools, who would have the authority to investigate abuse, waste and fraud in schools. The investigator general would be appointed by the State Board of Education, present annual reports of all findings to them, and have wide investigative and subpoena powers and the power to refer investigation subjects to law enforcement.

Why is it bad?

There’s nothing wrong with investigating waste, fraud, or abuse. But, apart from a few legitimate concerns, the responsibilities of the proposed investigator general are a mix of things better left to law enforcement (grooming, trafficking) and issues pulled straight from right-wing talking points. The inspector general would specifically be charged with investigating violations of parental rights, and with making sure that schools aren’t teaching “critical race theory” or failing to present “balanced” perspectives on current events. The inspector would also be charged with investigating possible violations of the state’s obscenity laws or laws against distributing material “harmful to minors” (see above).

You see the pattern, right? Along with the bills changing the definition of “harmful to minors” and repealing the affirmative defense for distributing such material, this bill is part of a package proposed by the state GOP’s “Stop Sexualizing Texas Kids” committee, and its intent is clear: to demonize public schools and educators and write into law the assumptions behind current right-wing paranoia.

With HB 1025, the people behind those other book-banning laws are hoping to create a politicized Grand Inquisitor who will do the punitive work that that law enforcement and local school boards so far haven’t—or, at least, that the office will further terrorize educators into self-censoring.

Senate Bill 86 (Bob Hall) and House Bill 976 (Steve Toth)

What do they do?

We have two proposed knockoffs of Florida’s infamous “Don’t Say Gay” law, each of which heavily restricts (without defining), “instruction regarding sexual orientation or gender identity.” Steve Toth’s House bill mimics Florida’s law in forbidding such restriction for any students in kindergarten through 8th-grade and requiring “age-appropriate” instruction in such topics for all grades. Hall’s Senate bill goes even further, forbidding any instruction regarding sexual orientation or gender identity for any student, no matter the grade level.

Hall’s bill also requires schools to notify parents if a student student’s “perception of the student’s biological sex” “is inconsistent with the student’s biological sex as determined by the student’s sex organs, chromosomes, and endogenous hormone profiles.” In other words, it’s a forced-outing bill—if a teacher is aware that a student is trans or nonbinary, he or she is required to report that to the student’s parents.

Why are they bad?

So many reasons. Let’s start with the Don’t Say Gay part. Proponents of the bill will ask why teachers need to be “instructing” young students on sexuality or gender identity—but of course the actual targets of this bill are lessons and books designed to foster inclusion, to make LGBTQ students or students with LGBTQ family members feel a little less alone. In Texas, we have already seen attempts to ban books like Jacob’s New Dress or Lily and Dunkin; those efforts would likely get a big boost if these bills become law.

And, because neither bill defines “instruction,” they can be interpreted broadly to include a teacher mentioning her wife, or a reading assignment that simply includes a gay character. In Florida, a teacher was investigated by both her district and the Florida Department of Education for showing a Disney movie related to her curriculum that happened to include a married gay couple (the teacher has since left her district, citing the state’s politics).

Finally, while it’s not directly related to books in schools, don’t sleep on the damage the forced-outing portion of Hall’s bill can do to students and classrooms. There are a number of reasons (including fear of abuse) a student might be “out” at school but not at home, and making teachers into gender police of their students is a horrible idea.

House Bill 629 (Terri Leo Wilson)

What does it do?

Representative Terri Leo Wilson, a former teacher and member of the State Board of Education, is taking another crack at a measure that would require Advanced Placement courses in the state to be vetted by the SBOE to ensure compliance with “school laws of the state.” It echoes a battle that played out in Florida two years ago, when Ron DeSantis threatened to ban AP African American Studies from the state on the allegation that it contained Critical Race Theory. Since 2023, Texas law has forbidden instruction that might suggest that “an individual should feel discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress on account of the individual ’s race or sex.” These are, in part, the grounds on which Florida (and later Arkansas and South Carolina) rejected the AP African American Studies course.

And Leo Wilson has expressed a lot of concern about “wokeness” infecting Texas schools, and thinks that it’s a particular issue with AP classes. “They’re targeting the top 10% of those kids,” she told the Texas Scorecard. “The five writers for the College Board are far leftists. One is like the critical race theory professor in Alabama, I think it is. But these are people who are not mainstream, who have a social agenda that they want to present to students.”

Why is it bad?

Look, I’m no big fan of the College Board, which Annie Abrams has rightly criticized for the damage it has done to the American education system. But AP courses are written by college professors and meant to reflect the knowledge students will receive in university courses—the ideas they’ll debate, the texts they’ll wrestle with, the perspectives they’ll consider after leaving high school.

At some point, learning itself is incompatible with the suppression of ideas. You can’t have both. And you can’t have a college-level class if you don’t ask students to consider ideas that challenge their worldview.

The results of the battle in Florida are instructive. Even after the College Board made significant revisions to AP African American Studies that specifically addressed the concerns raised by the Florida governor, the course was still banned in the state in 2023. South Carolina and Arkansas followed suit. If this bill passes, it’s likely that our highly politicized State Board of Education would reject that course and possibly others.4

House Bill 955 (Steve Toth)

What does it do?

In Texas, school board elections are non-partisan, meaning that candidates do not run with party affiliation and are not labeled as “Democrats” or “Republicans” on the ballot. Toth—whose policy strategist, Cassandra Crowe, is behind book bans across the Houston suburbs—has proposed a bill that would change that, requiring trustee candidates to run with party affiliations and be chosen through a primary system.

Why is it bad?

Put aside the fact that public schools are not supposed to be partisan, and school boards have traditionally been one of the few places where Republicans and Democrats have worked together without the division that characterizes so much of contemporary society. There’s also a cynical and nakedly partisan reason for this bill: For several election cycles, extremist candidates, especially those who support school book bans, have struggled at the polls. Book bans are not politically popular in Texas. But Republicans are.

Book-banning candidates in Texas have fared best when they are able to activate voters’ partisan instincts in heavily Republican areas (which includes most districts in the state). They do this by running as the “true conservatives” in the race and painting their opponents—even staunch Republicans—as liberals or progressives. Toth’s home district of Conroe ISD is an example of a place where this strategy succeeded in delivering a divided district a 7-0 book-banning majority.

What’s more, we’ve seen how the pressures of a partisan primary have pushed the Texas Republican party to embrace positions far to the right of the average Texas voter, and this bill would require school board candidates to participate in a party primary process. So HB 955 would not only lead to more extreme candidates in the general election, it would also then reward extreme candidates on the right with an electoral advantage. That would mean more book bans and fewer protections for students.

HB 183 is getting, rightly, getting a lot of publicity. See my colleague Laney Hawes’s comments in this piece for CBS Austin.

The bill would also remove the word “utterly” from the phrase “utterly without redeeming social value for minors.”

AP English Literature and AP Spanish Literature, for example, would both likely be on the chopping block. While AP English Literature does not require any books or include a specific curriculum, its year-end exam regularly includes books that have been challenged or removed from schools across the state (and could be illegal in Texas schools if HB183 passes). AP Spanish Literature, in contrast, does include a list of required texts, some of which could be construed as violating Texas law.

I think Abbott and the Texas legislature are taking notes from the Taliban. The next thing will be banning women from school after age 10 (and only religious madrassas at that)

And it ends in banning women from even speaking to each other (yes, this actually happened)

Anyone genuinely concerned about censorship should check out ScreenItFirst.com — a humble project born from the idea that it takes a village to raise a reader. It’s not about banning books. It’s about giving everyday people a place to share direct snapshots from books so others can decide for themselves. If a story doesn’t align with your family’s values, you can skip it, save time, and help preserve innocence for the next family too. #preserveinnocence