On Wednesday, the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals upheld a district court judge’s injunction barring most of HB 900, the book-removal bill authored by State Representative Jared Patterson and signed into law by Greg Abbott last summer. It prevents the most onerous part of the law—the requirement that book vendors rate every book ever sold to schools for sexual content—from taking effect. For now.

Judge Don Willett, a Trump appointee, wrote: “The question presented is narrow: Are Plaintiffs likely to succeed on their claims that READER violates their First Amendment rights? Controlling precedent suggests the answer is yes.”

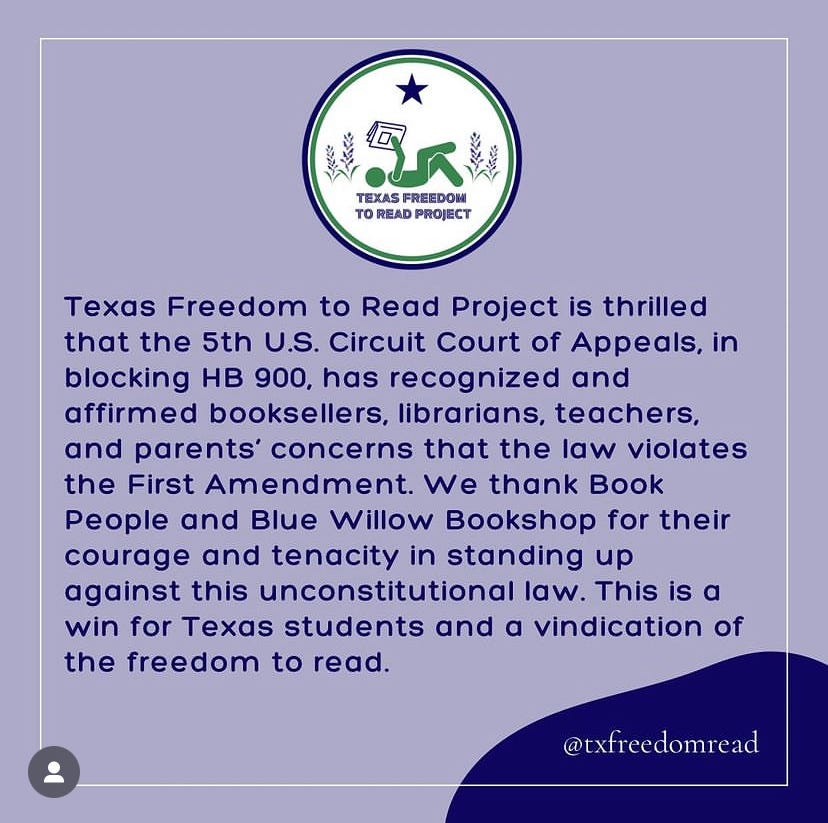

This is how the Texas Freedom to Read Project responded:

I’ve had a few days now to read the decision and to scan reactions to it from folks across the political spectrum. Disclaimer: I am not a lawyer. I’m writing this as a teacher with a pretty good idea of how the law would play out in schools if allowed to take effect. I welcome corrections and clarification from those with more legal knowledge than me.

That said, here are my first three thoughts on the ruling:

We avoided a nuclear strike on the state’s school libraries.

The ruling is great news. HB 900 threatened not dozens, not hundreds, but thousands of books in Texas schools. The grounds for removal, “sexual explicitness,” was vaguely defined, and the bill punished raters with the threat of massive business losses for anything other than a maximalist interpretation of the term.

The combination of a poorly defined term and incentives to err on the side of caution in interpreting it is exactly the formula that led Florida’s Escambia County to pull nearly 1600 books—including dictionaries, Bill O’Reilly books, and countless classic works of literature—for review. But under HB 900, vendors’ ratings would have applied statewide.

I’ve written over and over and over what this would mean for teaching in literature in Texas. AP Literature would become extremely difficult to teach, since many of the type of books the College Board expects students to read contain content that could be construed as “sexually explicit.” Beyond that, Texas students could lose access to classical mythology, to critical editions of otherwise innocuous texts, to memoirs from sexual assault victims, and to books that high-schoolers have been reading for generations.

So this was undoubtedly a win for Texas students.

The library standards remain in effect. What does that mean?

Proponents of HB 900 have tried to put on a brave face after their defeat, pointing out that the law’s library standards provision still stands.

It’s true: The State Board of Education approved standards in line with HB 900 last month. Those standards require schools to remove and refrain from purchasing any books that are “obscene,” “harmful to minors,” “sexually explicit” (as rated by vendors), “pervasively vulgar” or “educationally unsuitable.”1

Of course, without a statewide rating, those terms (except for “obscene” and “harmful to minors”2) are undefined, vague, and open to interpretation.3 Erin Anderson, a writer for the right-wing propaganda website Texas Scorecard, understood the basic issue: “The real issue is that adults no longer agree on what content is ok for children.” Proponents of the law think Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye is educationally unsuitable for high school students; AP English teachers, who have seen the text appear over and over again on their year-end test, disagree.

Where does that leave Texans? Essentially where we were before the bill was passed. To be clear, that is not a great place: book banners will continue to pressure districts to remove books, and now they’ll have a few more terms to lob as ammunition. Expect to hear a lot about educational suitability in the coming months.

Another way to frame it is that while we avoided the nuclear strike at the heart of HB 900, Texas school libraries remain under siege.

What’s Next?

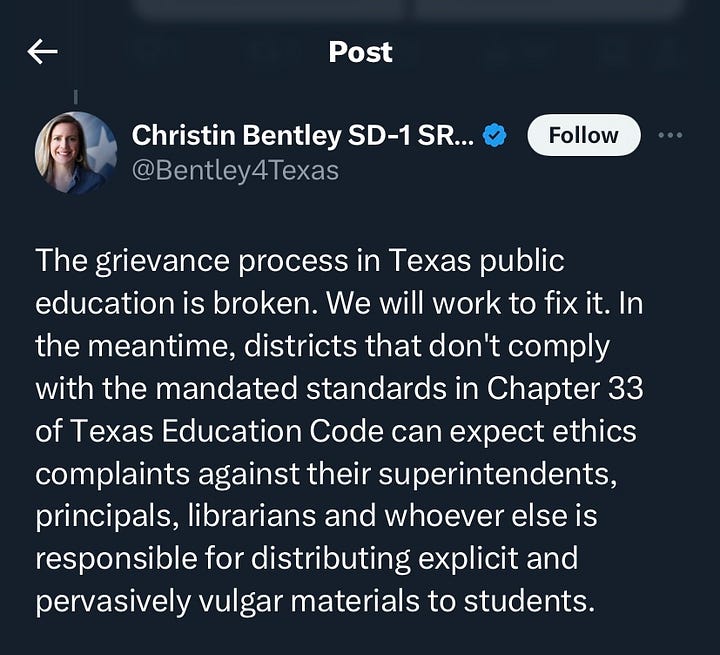

The people behind HB 900 have signaled that they intend to use the library standards as an excuse to file ethics complaints against educators who make available books they don’t like, thus threatening their certifications.

I have no idea if that will work, but it does reflect the basic nastiness of their reaction to this week’s rebuke.

The legal process for HB 900 will continue. The 5th Circuit remanded the case back to the district court, and Patterson says he hopes Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton will appeal Wednesday’s decision to the Supreme Court. But, as of now, the vendor rating portion of HB 900 is not the law of the land.

Most of all, Wednesday’s ruling underscores the importance of school board elections—the next batch of which will be held on May 4. The fight for the freedom to read in Texas will continue book by book and district by district. Without statewide ratings, trustees and district leaders will decide what phrases like “educationally unsuitable” mean.4 Reactionary boards, like the trustees of Spring Branch ISD, have already used the term to restrict books with little or no sexual content. And even moderate boards—like those in Plano, McKinney, and Fort Worth—have given into pressure from extremists and removed books en masse over the objections of parents and educators.

The state’s book banners know this, which is why so many of them have responded by pointing directly at school boards and the upcoming elections. Tara Petsch, the leader of Gillespie County’s Moms for Liberty chapter, told the Texas Scorecard, “School board trustees must start protecting children.”5 And Christin Bentley, a Republican operative who was instrumental in getting HB 900 passed, tweeted, “Trustees who still haven’t ensured explicit materials are out of their schools are complicit in the sexual grooming of children. Vote them out.”

The filing period for school board candidates opened this week—coincidentally, the same day the 5th Circuit issued its ruling. It closes on February 16. I’ll have my Book-Loving Texan’s Guide to the elections up soon after that.

These standards are more restrictive than previous legal guidance. In their plurality decision in Island Trees School District v. Pico (1982), the Supreme Court held that school districts may remove books that are pervasively vulgar or educationally unsuitable; the new library standards say that schools must remove such books.

“Obscene” and “harmful to minors” are both clearly defined in Texas law, but no books in Texas schools meet those definitions. A book that’s legally obscene falls outside of the protection of the 1st Amendment—it’s not something anyone can pick up at Barnes & Noble, like Gender Queer or All Boys Aren’t Blue. The book banners know this, which is why, in the last legislative session, they tried unsuccessfully to change those definitions in the law. (They are promising to try again next session)

“Sexually explicit” is extensively (though not clearly) defined in HB 900, but to quote Judge Willett’s decision, “The statute requires vendors to undertake contextual analyses, weighing and balancing many factors to determine a rating for each book. Balancing a myriad of factors that depend on community standards is anything but the mere disclosure of factual information. And it has already proven controversial.”

Patterson told conservative talk radio host Mark Davis this week that he will continue to try to push a rating scheme through the legislature. Since it’s clearly unconstitutional to force vendors to do it, Patterson is now suggesting it may be done by “some bureaucrat sitting in a cubicle somewhere going through all these books looking for pornography.”

In 2023, Moms for Liberty Gillespie County supported candidates in the school board elections for Fredericksburg ISD and Kerrville ISD. Both lost.