This story out of Argentina is both frightening and fascinating. Frightening because it shows how effectively Moms-for-Liberty-speak has spread and become the lingua franca for book ban attempts around the world; fascinating because it illustrates so clearly what we’ve been saying for years here in Texas: namely, that such attempts aren’t really about the books themselves and that these attacks on a few books put at risk the entire library.

I learned about the story from the podcast El hilo. PEN International is also on top of it.

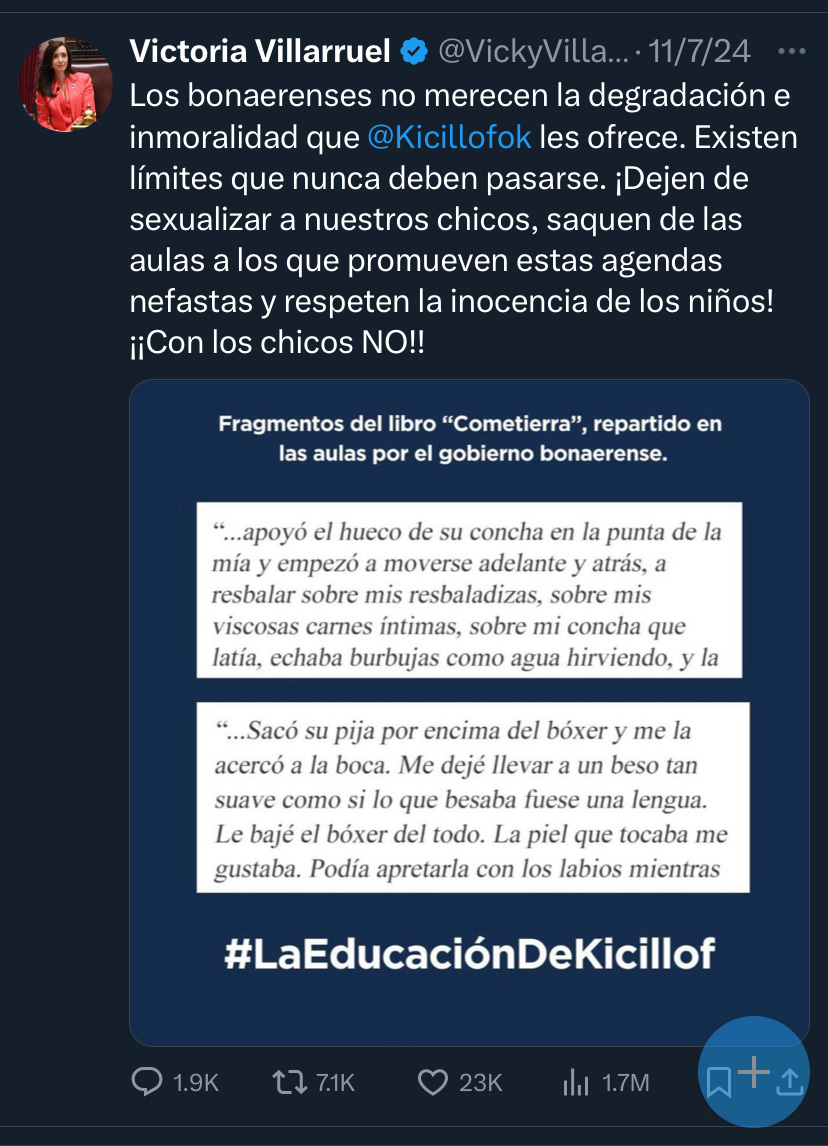

Here’s the timeline: In October, a group of parents at a private school in Mendoza got a high school teacher fired for assigning the award-winning novel Cometierra, by Dolores Reyes. Not long after, Vice President Victoria Villaruel launched a social-media campaign against the book and three others that were purchased for high school libraries in Buenos Aires. Her tweets were shared by Argentina’s president Javier Milei, a self-described anarcho-capitalist and admirer of Donald Trump. Then a relatively unknown group, the Fundación Natalio Morelli, filed a public criminal complaint against the General Director of Education in Buenos Aires, Alberto Sileoni, accusing him of abuse of authority, distributing pornography to children, and corruption of minors.1

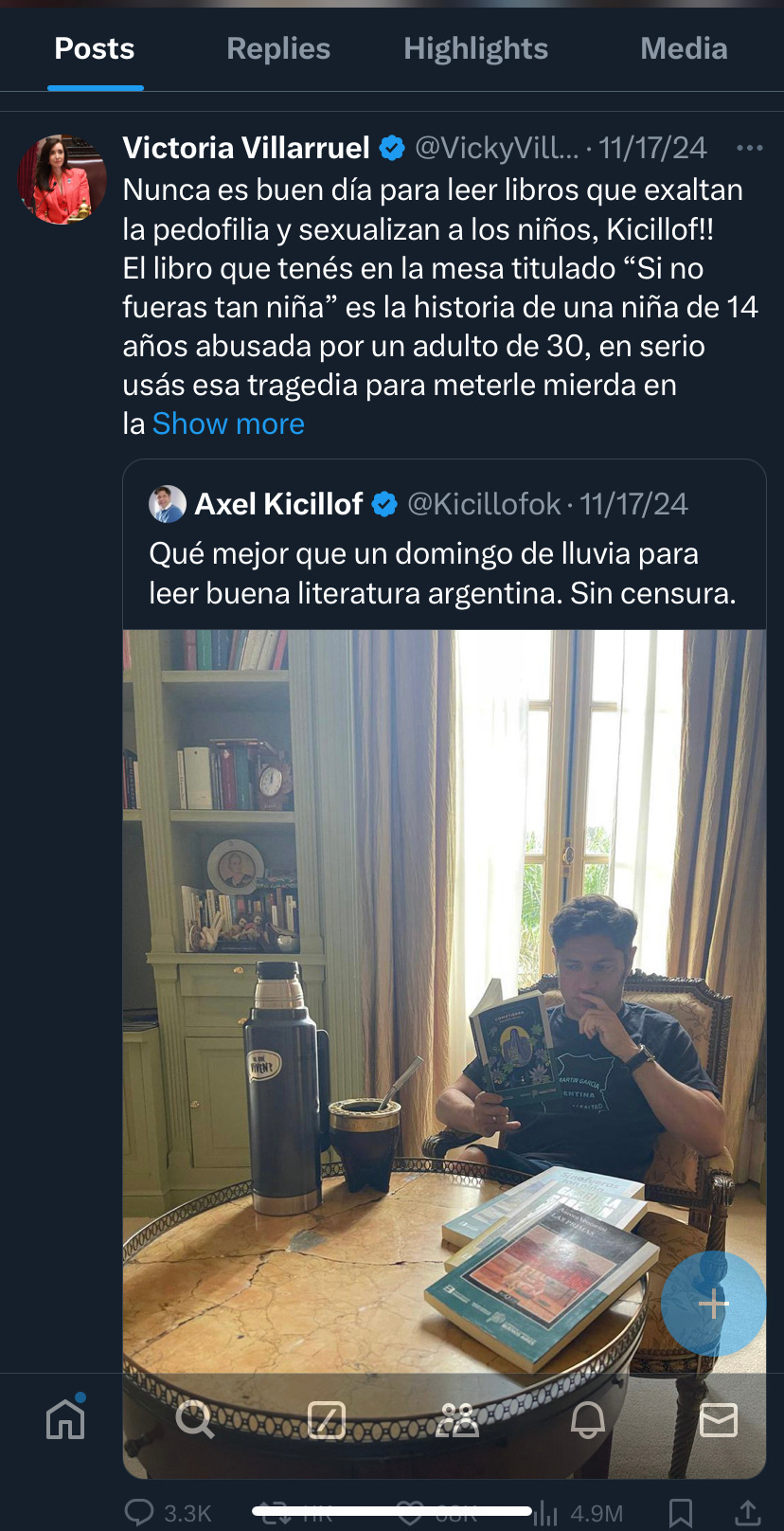

Notably, the regional government of Buenos Aires is controlled by Milei’s political opponents, and Villaruel’s attacks have been aimed at not just the books, but at Axel Kicillof, the provincial governor of Buenos Aires, who appointed Sileoni.

Last month, hundreds of authors, including Reyes, staged a public reading of the four challenged books at the Teatro Picadero, a symbol of resistance to the military dictatorship that controlled Argentina from 1976-1983 and engaged in widespread censorship while terrorizing suspected “leftists.” Author Claudia Piñeiro, who helped organize the reading, told El hilo, “The best way to respond to something like this is to read” the books that the censors don’t want people to read.2

Cometierra is an acclaimed 2019 novel about the epidemic of femicide that has roiled Latin America, including Argentina, for decades. Challengers have objected to two scenes in the novel in which the protagonist, a young woman with a supernatural ability to see the fates of those murdered, describes her sexual experiences. Besides Cometierra, the books under attack are: Si no fueras tan niña, by Sol Fantín, a memoir in which the author recounts sexual abuse she experienced as a teenager; Las aventuras de la China Iron, by Gabriela Cabezón Cámara, a feminist re-telling of the classic Argentine epic poem Martín Fierro, in which the protagonist, Fierro’s wife, falls in love with a woman; and Las primas, by Aurora Venturini, an irreverent takedown of Argentine society told from the perspective of a dyslexic young woman.

You probably already see parallels to the book-banning movement in the United States. The four books challenged are all written by women; all, in a sense, are feminist texts. The books deal with sexual abuse and violence, with LGBTQ relations, and abortion. While the banners claim that they’re merely concerned about sexual content, their attacks are transparently political and ideological.

And the Argentines are borrowing US rhetoric and tactics, too. Both Villaruel and Bárbara Morelli, the leader of the Fundación Morelli, use the term “niños” in a slippery way, making it seem like these books are being given to elementary students, when in fact they’re non-required reading for advanced high school and university-level students. And, like book-banners in the US, they claim that books depicting sexual abuse from the victim’s perspective are somehow advocating for that abuse. Villaruel’s tweets could have been copied, Google-translated, and pasted from any Texas Mom for Liberty: “Stop sexualizing our kids, remove from the classrooms those that promote these nefarious agendas, and respect the innocence of the children!” she wrote on November 7.3

But the similarities go beyond shared tactics, rhetoric, and targets. We've said for years that the implications of book-banning battles in the US extend past the list of 5 or 14 or 55 or 676 books up for debate in any one district. I’ve written over and over again that in the current censorious climate no book is safe. Texas Freedom to Read Project has tracked exactly what that means: libraries that stop purchasing books; teachers forced to empty their classroom libraries; books removed that have no sexual content at all, or that are recognized classic texts. And in the US, the forces pushing for the removal of books dovetail with a culture that devalues literature more generally, exemplified by districts like Houston ISD, which shut down its libraries in a misguided attempt to boost test scores.

The push for censorship in Argentina builds on the same impoverished view of literature and education, and seems to be headed in the same direction. Argentine students should only read “educational” books, said Morelli, by which she means nonfiction books about subjects like math or biology. “Si quieren leer ficción, que lean en su casa.” If they want to read fiction, they should do it at home.

The Fundación Natalio Morelli says its mission is to protect “the wellbeing of boys, girls, and adolescents.” El hilo describes the group as a foundation with links to the country’s extreme right-wing and the Milei government.

As in the US, where Authors Against Book Bans has been an indispensable voice in the fight against censorship, authors in Argentina have led the resistance against the Milei government’s attacks on books. Piñeiro, in particular, has provided incisive commentary on the larger implications of the attack on Cometierra.

Villaruel also borrowed the Moms for Liberty tactic of posting out-of-context passages from Cometierra to “prove” its unsuitability. But, like many Moms for Liberty, her tweet also proved that she hadn’t read the text, since one of the two passages she posted was actually from a different book, Las aventuras de la China Iron.