Are we still allowed to teach literature in Texas (or Florida, or Tennessee, or Missouri, or Louisiana) schools?

The question might seem over-dramatic, but one thing has struck me about the book-banning movement as I’ve watched it grow over the past two years: it comes from a fundamentally destructive impulse.

The groups, politicians, and activists behind the movement can tell you what they want to take out of our schools—books, ideas, “activist teachers,” often their own children—but they never say what they want to put in in their place. A book reconsideration form in Conroe ISD asked book challengers to suggest a replacement for the book they wanted banned: “Finding the appropriate content falls under your duties,” said one respondent.

I watched hours of school board meetings in dozens of districts in 2022, and the mob members at public comment only ever seem to offer one answer to the question of what they think schools should do. “Go back to basics,” they say. “Reading, writing, math, and science.”

But when they say “reading and writing,” they mean it in only the most literal sense: they want graduates to be able to read a job application and string together grammatical sentences in order to fill it out. And basics are great! Basics are important! But I’ve never seen in these groups any concern for what we actually try to do in high school English classrooms. No concern for wrestling with ideas, no concern for critical thinking; no concern, in short, for the teaching of literature.

In the summer of 2021, at the start of the anti-CRT panic, I wrote a post on my Medium page asking if it was still possible to teach James Baldwin. I noted that I often give an assignment in which I ask students to consider his message in “A Talk to Teachers,” including the idea that the job of teachers of Black children is to teach them that American society is a “criminal conspiracy” meant to destroy them. I ask my students if he’s right. I’ve had students argue intelligently both ways.

A year and a half later, the answer to my post is clear: No. I could not assign James Baldwin now, at least not if I were a teacher in a district controlled by Moms for Liberty board members and I wanted to keep my job. Not “A Talk to Teachers,” not Notes from a Native Son, not If Beale Street Could Talk. Certainly not Giovanni’s Room.

Of course, the question wasn’t just about Baldwin. The whole sweep of the African-American literary tradition includes ideas that have been demonized as “critical race theory.” How can you teach Nella Larsen without talking about white privilege? Or Invisible Man without talking about structural racism?

The point was that the thrust of the book-banning movement in its 2021 incarnation made teaching Black literature virtually impossible, or at least something that had to be done with fingers crossed, hoping the wrong student wouldn’t record the wrong part of a class discussion out of context, or that the wrong parent wouldn’t flip to the wrong page in the wrong beautiful, important piece of literature.

I had no idea then that it was about to get worse.

At the end of 2021, the anti-CRT scare morphed into a “porn in schools” scare. The groups that had been complaining about Ibram X. Kendi and Jason Reynolds turned their attention to removing from schools any books that fell into four broad categories: 1) works of literature, no matter how acclaimed, that frankly portrayed sexual trauma, especially from the victim’s perspective (The Bluest Eye, Out of Darkness, The God of Small Things); 2) young adult novels that realistically depicted teenagers’ sexual thoughts or conversations (Looking for Alaska, The Perks of Being a Wallflower); 3) sex-ed books (It’s Perfectly Normal); and 4) books, however tame, with messages of acceptance for LGBTQ youth (Drama, Jacob’s New Dress).

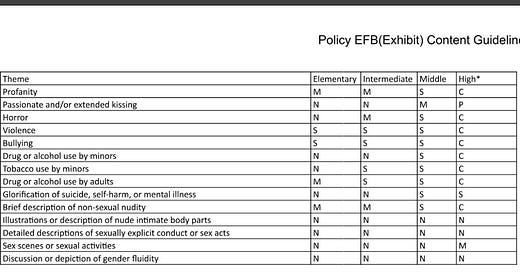

That last category gives the game away: it’s not about “sex,” but about ideas with which the groups pushing book bans disagree. And look at Keller ISD’s criteria for materials selection: In addition to sex and “gender fluidity,” books are scrutinized for drug or alcohol use, for violence, and for “glorifying” suicide or mental illness. This isn’t just a Keller thing: Gary Paulsen’s Hatchet—a favorite book of mine in 5th grade—has been challenged in Tennessee for being too “dark.”

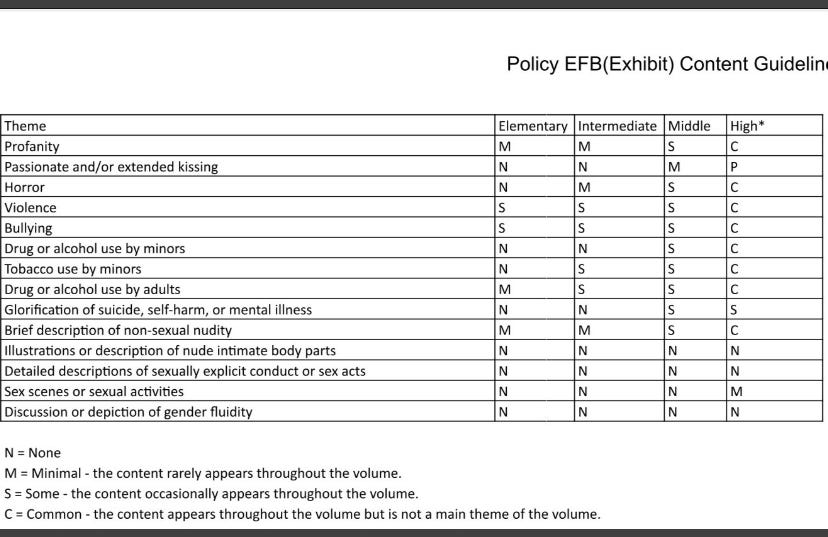

As the list of verboten topics expands, the list of teachable texts shrinks. On Twitter a few weeks ago, I posted Free-Response Question 3 from last year’s Advanced Placement Literature exam and pointed out that teachers couldn’t assign nearly half of the College Board’s suggested texts in many American school districts.

But even that doesn’t get at the stakes of the issue. Quite simply, in this censorious era, there are no safe texts. No book is safe from a challenge.

Look again at that list from the College Board, and remember that the same groups banning books are scouring teachers’ lesson plans and social media for things to be outraged about. Think how easily a discussion of Othello or Jane Eyre or Crime and Punishment could veer into dangerous territory. In 2022, a New Jersey teacher was attacked in conservative media for the discussions she fostered in a unit on Romeo and Juliet.

Again: no book is safe.

Literature is supposed to challenge and upset us. Agnes Callard made this point when she argued last summer that art is for seeing evil. That doesn’t mean art is evil; to the contrary, art, including literature, is where we can process safely the idea of evil and work out our responses to it. Art shows us what we don’t want to confront in real life. Even literature that’s ultimately consoling or joyful presents its joy or consolation against the presence or possibility of suffering. “I can name many works of fiction in which barely anything good happens,” Callard writes, “but I can’t imagine a novel in which barely anything bad happens. Even children’s stories tend to be structured around mishaps and troubles. What we laugh at, in comedy, is usually some form of misfortune.”

Ashley Hope Pérez, whose novel Out of Darkness is one of last year’s most frequently banned books, said something similar in an interview with NPR: “[L]iterature from the Bible to Chaucer to Shakespeare to Faulkner deals with difficult topics because those aspects of life are the materials literature... it's not to be provocative or to distress anyone, but because when we want to write about human experience honestly and completely, we have to include the pain of being a person.”

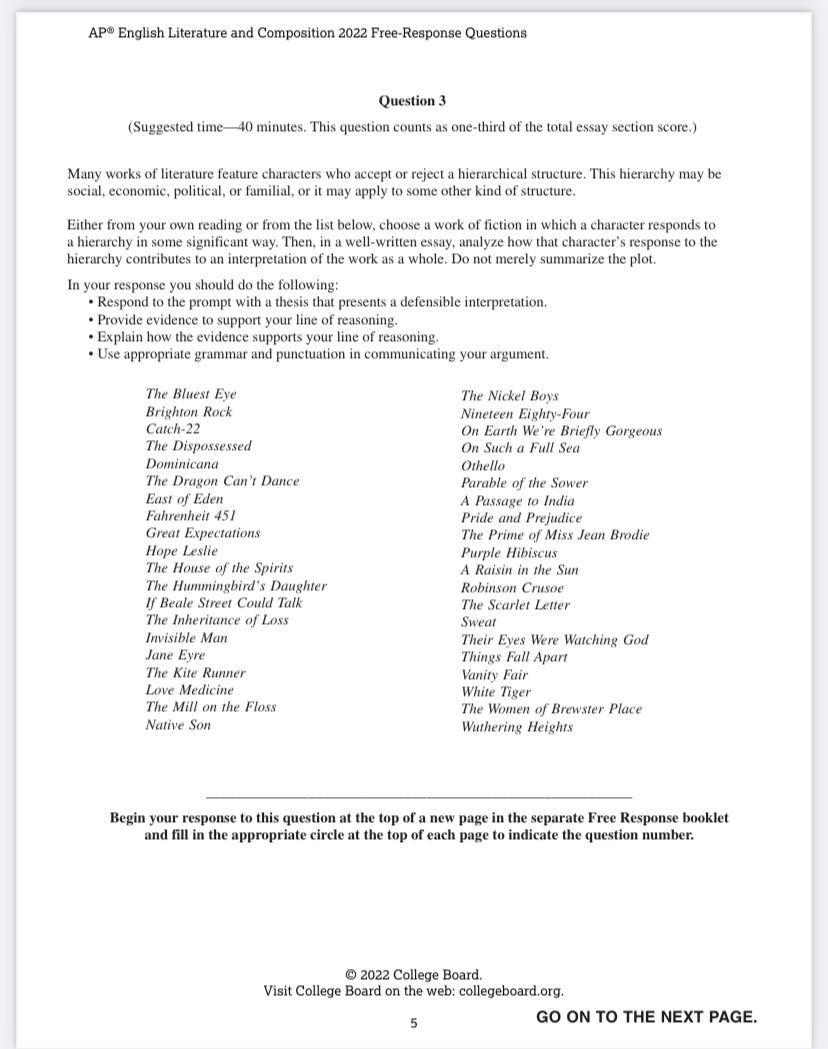

That might seem obvious, but it puts the whole idea of literature at odds with activists and politicians who say their first priority is “preserving the innocence” of students. So you get taped-off classroom shelves and libraries that require a permission slip to enter. Those are the stakes—not just the one or two (or thirty or forty) books on the chopping block in any given district.

COMING NEXT: What is going on in McKinney ISD?

Thanks for validating the concerns I have had and been voicing in the book banning arena in McKinney ISD. The excerpt from the Perez interview brought to mind another great quote from Oscar Wilde: “The books that the world calls immoral are books that show the world its own shame.”