A new bill could ban Huck Finn and "Letter from Birmingham Jail" from Texas public schools

First notes on SB13

On Wednesday, Texas State Senator Angela Paxton filed SB13, a bill that was listed as one of Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick’s legislative priorities for this session with the purpose of “guarding against inappropriate books in public schools.”

The full text of the bill is available here. Every Republican member of the Senate is listed as co-author.

In some ways, SB13 echoes a similar bill Paxton filed last session, which failed, but it also builds on Jared Patterson’s HB900, the so-called “READER Act,” which was signed by Greg Abbott in 2023 and is currently in constitutional limbo as it works its way through the courts.

SB13 does several things. It establishes “Library Advisory Councils” in every school district, apparently modeled after SHACs, which would have broad authority over what books would and wouldn’t be allowed in district libraries. It also purports to expand parental rights through a number of measures, like ensuring schools have their library catalogs online and requiring schools to notify parents about every book their child checks out. SB13 also adds several layers to the process a district must undergo to order library books. And it creates two new categories of books that are forbidden from Texas schools under state library standards.

Let’s start with the last two elements of the bill, which I think are the most damaging to Texas students.

HB900, the anti-book bill passed in the last legislative session, created library standards that forbid schools from having books that are “harmful to minors,” “pervasively vulgar,” “educationally unsuitable,” or rated as “sexually explicit.” Except for “harmful to minors,” which is defined in the Texas penal code1, all of those are vague, undefined, and debatable terms. In fact, judges have repeatedly pointed out the difficulty of applying those terms to books, and that’s part of why sections of the law have been found likely unconstitutional.

Instead of clarifying those terms, SB13 adds two new categories of books to be banned from schools: those that have “indecent content” and those that have “profane content.” Indecent content is content that “portrays sexual or excretory organs or activities in a way that is patently offensive.” Profane content “includes grossly offensive language that is considered a public nuisance.”

You’re probably thinking: this doesn’t fix the problem. “Indecent,” “profane,” “patently offensive” and “grossly offensive” are also subjective, debatable terms. That’s true.

What it does, though, is greatly expand the number of books that can be banned from schools.

First, note the shift: HB900 banned books that are rated sexually explicit; SB13 also removes books that have indecent or profane content. Are vs. have. In other words, to determine whether or not a book is allowed in schools, you no longer have to consider the work as a whole—now, if a book contains offensive language (a few curse words here or there, for example), it’s forbidden.

Second, notice how much more capacious those two new categories are than HB900’s. Content no longer has to be sexual to get a book banned—merely offensive.

What does that mean for high schools?

I’ve taught “Letter from Birmingham Jail” for years in my AP English classes, but there are certain passages I make sure students don’t read out loud in class. Why? Because they contain racial slurs—i.e., “grossly offensive language that is considered a public nuisance.” Under the plain language of SB13, “Letter from Birmingham Jail” would be banned from Texas schools.

For the record, I don’t think that proponents of this bill intend to use it to remove MLK’s writing from schools. But it’s not just MLK; this law could ban Mark Twain or Ralph Ellison or Richard Wright or To Kill a Mockingbird or just about anything Faulkner wrote. These guidelines would exclude so much of the literature that makes up advanced high school English classes. As Texas Freedom to Read Project has documented, it is very hard to teach literature in Texas after HB900; this new law would deal a staggering blow to educators who are already struggling.

But it gets worse. SB13 also mandates that all districts in the state adopt an arduous process for purchasing new library books. All lists of books to be purchased would have to be made public for at least 30 days before purchase, and then approved at a public board meeting after consultation with a Library Advisory Committee (which is only required to meet twice a year). Board members could vote to veto any proposed purchases.

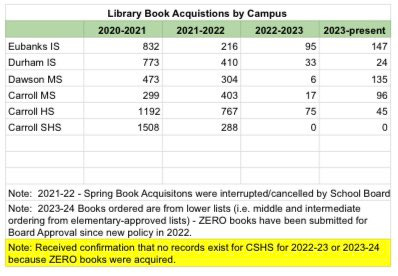

We know what these requirements will do because several districts in Texas have already adopted them. Carroll ISD in Tarrant County—one of the first epicenters of the state’s anti-book earthquake—was among the first to require a 30-day public listing of purchases and board approval for all individual titles. The results were dramatic:

Carroll ISD’s policy was adopted in July 2022, and then fully implemented halfway through the 2022-2023 school year. The district went from ordering 1500 books for Carroll Senior High School in 2020-2021 to 0 books in 2023-2024.

Let me repeat that: The district ordered zero (0) books for its senior high school for at least two school years.

There are other troubling aspects of SB13, too. The bill would require districts to pull challenged books off of shelves while they’re being reviewed, for example, and librarian groups have pointed out that a district advisory council would be cumbersome for very large districts or small, rural ones.

The bill also requires districts to notify parents of every book a student checks out. That’s already policy in several districts around Texas. Most parents I’ve talked to in those districts, especially parents with multiple kids, find the constant notifications annoying.2

On a more constructive note, SB13 requires districts to post their library catalogs online, and allows parents to submit lists of books that they don’t want their kids reading. Those are great ideas.

But we can achieve transparency and parental rights without all of the destructive measures contained in SB13. Make no mistake: SB13 would be catastrophic for education in Texas. Too many of our schools are turning into book deserts, and SB13 would speed up that process.

There are no books in schools that meet the legal definition of “harmful to minors,” which is a stringent legal term that requires the whole text of a work to be taken into consideration. Texas book banners are currently trying to change the definition of “harmful to minors” in the Texas Penal Code, though.

Parents: If you want to know what your kids are reading, a better and more rewarding way to find out is to talk to them.

Anyone genuinely concerned about censorship should check out ScreenItFirst.com — a humble project born from the idea that it takes a village to raise a reader. It’s not about banning books. It’s about giving everyday people a place to share direct snapshots from books so others can decide for themselves. If a story doesn’t align with your family’s values, you can skip it, save time, and help preserve innocence for the next family too. #preserveinnocence

Thank you! I am testifying against it again.