I do this weird thing when someone starts shouting out-of-context quotes from a book I haven’t read, demanding I defend its inclusion in school libraries: I read the book.

I know, I’m old-fashioned. Eccentric even.

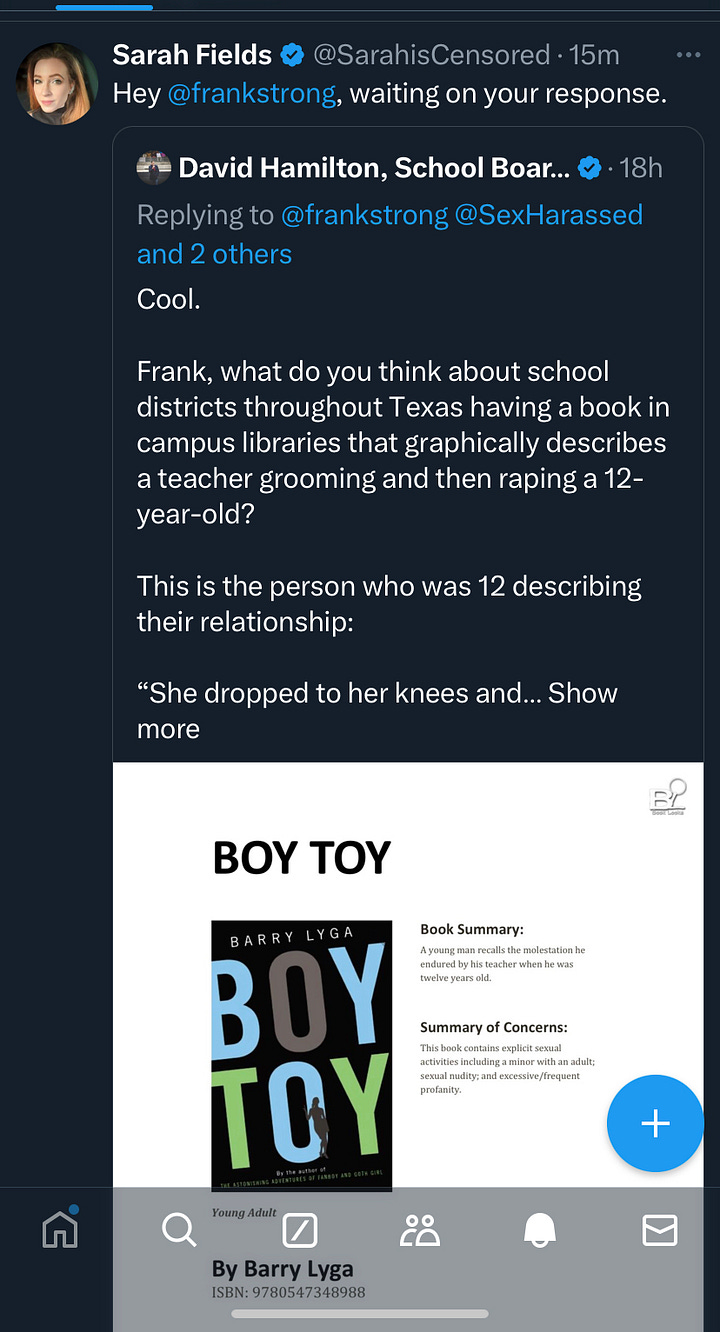

Last week, right-wing internet personality Sarah Fields quote-tweeted a post from an internet troll who likes to shock people with passages from books he hasn’t read but would like removed from public schools.1 In this instance, that person had posted a rating of Barry Lyga’s 2007 YA novel Boy Toy from the Moms-for-Liberty-affiliated website BookLooks.org, along with two excerpts from the book, clearly taken from the website. “Frank, what do you think about school districts throughout Texas having a book in campus libraries that graphically describes a teacher grooming and then raping a 12-year-old?” he asked. “Hey, @frankstrong, waiting on your response,” said Fields.

I don’t owe the internet’s hate machine anything, but I do try to stay on top of the books that are being challenged in Texas, and this was a book I hadn’t read or even heard much about. The Austin Public Library has an e-book edition available, so I checked it out and read it over the weekend.

Guess what? The BookLooks rating misses a ton of important information about the book, and the people using this book as a cudgel to attack freedom-to-read advocates are being deceptive.2

One thing my internet stalker said was true: Boy Toy does depict the grooming and eventual rape of a twelve-year-old boy by his middle-school history teacher.

That said, the book isn’t about the grooming and rape of the novel’s main character, Joshua. It’s about the aftermath of that abuse, and the novel details the devastation, confusion, and damage sexual abuse wreaks on a young victim. Lyga says that he was thinking about the cultural hypocrisy in society’s reaction to abuse cases in which the perpetrator is a woman and the victim is a boy—how such victims are often viewed as “lucky” or how those cases aren’t always taken as seriously as rape when the genders are reversed. “But rape is rape,” Lyga says about his decision to write the book, “and I had a feeling that maybe those kids weren’t so lucky after all. And maybe I could tell that story.”

The body of the novel starts with its protagonist, Joshua Mandel, not at twelve years old but at eighteen, about to graduate from high school. Outwardly, Josh is successful: he’s incredibly smart and has never had trouble with his grades, and he’s also athletically talented, a star baseball player. But the reader quickly realizes that Josh is an emotional wreck. He’s angry at the world, he lashes out violently at those around him—in the first chapter he punches out his baseball coach. He worries that everyone around him knows about what happened to him five years before and judges him for it, and he suffers debilitating flashbacks (he calls them “flickers”) to his abuse. As the novel opens, the former history teacher who abused him is about to be released from prison, and Josh has a panic attack in the supermarket when he sees a woman who resembles his abuser from behind.

Most of all, Josh struggles to connect with girls and can’t maintain a normal high school relationship—and this has been true ever since his abuse. “How nice it would be to just hold hands with her,” he thinks about a potential girlfriend. “Just hold hands. But it can never just be that anymore, can it?”

Lyga intersperses the novel’s storyline with transcripts from Josh’s sessions with a therapist who both explains the process by which the teacher groomed Josh and explicitly names the damage she caused. “What Evelyn Sherman did to you wasn’t about intimacy,” the therapist tells Josh. “There may have been times that she made you feel like it was, but it was all about satisfying her needs. You were a means to that end.”

In the novel’s second section, Lyga does flash back in time to the grooming process, and this is where you’ll find most of the passages that BookLooks highlights. This section contains descriptions of abuse, and the scenes are stomach-turning, allowing the reader sees the teacher’s manipulations and deceptions, as well as Josh’s misgivings and feelings of guilt, shame, and confusion—the very feelings he deals with for the rest of the novel.3

In short, this is a book that makes clear to its readers the awfulness of grooming and the ways the process can play out. It also takes apart a dangerous narrative that can be harmful to male victims of female abusers. It’s not a perfect book, but it is a book that can help educate young readers about sexual predation and build empathy and understanding for its victims.

Which raises some important questions about those who want to see it removed from schools. Who benefits when students can’t access books about the dangers of grooming? Who is put in danger by such removals?

These questions are even more pertinent since the attack on Boy Toy is part of a pattern of attempts to ban books by and about the victims of sexual violence. According to PEN America’s 2023 study on book bans in America, 48% of all books challenged in school libraries in the previous year included instances of violence or physical abuse, and another 42% covered topics of health and well-being.4

The same person who demanded I defend Boy Toy has also challenged in his district Patricia McCormick’s Sold, a novel about child trafficking, and A Stolen Life, Jaycee Duggard’s memoir about the sexual abuse she endured. And two of the most challenged books in Texas are Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye and Laurie Halse Anderson’s Speak.

Shiwali Patel of the National Women’s Law Center has written an important piece that lays out the consequences of this phenomenon. She writes:

[B]anning these books signals there is something shameful and obscene in talking about sexual abuse, even though so many people, including students, have experienced it. These bans further stigmatize and legitimize silence around sexual violence, sending a message to survivors that what happened to you doesn’t matter, and an even broader message that silence about sexual violence is preferred over awareness about it. And these bans prevent student survivors from accessing stories that reflect their experiences—often painful and isolating experiences—barring many survivors from finding support, validation, and healing.

Again: Who benefits when students can’t access books about the dangers of grooming? Who is put in danger by such removals?

The obvious answers are that predators benefit from the removals of these books, and children are put at risk.

I want to be clear: I am not accusing the people who try to remove these books from schools of being groomers or intentionally endangering children. (Although I will point out that is exactly what they would do if they were writing about me.)

But I’m also not going to mince words about they’re doing. As Patel puts it, banning books like Boy Toy “means that more kids will get hurt, and more survivors will feel alone.” That is not something a decent person does to score political points.

This person, unfortunately, is a trustee in Fort Bend ISD. The Texas Freedom to Read Project has reported on his actions in that role. He has not responded in a healthy manner.

Shocker, I know.

If someone finds these scenes pornographic, that says more about them than it does about the book.

Reading the whole book is a radical act. Thanks for doing it.