“… the materials need to reflect the overall values of our community.”

How do you determine a community’s values?

In May, members of the Plano ISD community had the opportunity to weigh in on the culture wars that have engulfed school board elections for the past two years. Three conservative candidates—Lydia Ortega, Greg Jubenville, and incumbent Cody Weaver—leaned hard into censorship and anti-wokeness, campaigning on their opposition to drag queen story hour, “critical race theory,” and books with sexual content. At one board meeting, Ortega said, “I find that the books are sexualizing kids, making them vulnerable to molestation, rape, and pedophiles.” She recommended paying students to report on books with sex scenes.

All three candidates lost; none garnered more than 41% of the vote. The results were consistent with elections in neighboring districts—in McKinney, Richardson, Prosper, and Frisco, book-banning candidates were shut out of trustee positions. New Plano trustee Tarrah Lantz, who defeated Ortega, told the Texas Observer that her opponent’s over-emphasis on removing books reflected a misunderstanding of the priorities of her community’s voters. “When asked about things like safety and security at one of the first candidate forums,” Lantz told the Observer, “while my opponent said they thought the alleged existence of pornography in the library was our biggest issue, instead I talked about the bond money we have committed to safety and security and the addition of doors that can create barriers should a shooter be inside a school.”

But the election didn’t end attempts to remove books from Plano schools. In May, a few days before the election, Shannon Ayres spoke at the district’s monthly meeting. Ayres is not a resident of the district but is the Education Division Leader of the Collin County branch of a group called Citizens Defending Freedom (CDF), which has led book challenges in school districts around the state. At about the same time the district received formal challenges for 70 books. Ayres would become a frequent speaker at Plano ISD meetings—almost always asking the board to remove books—and the CDF contingent around her grew and grew, culminating in a dramatic meeting on October 3.

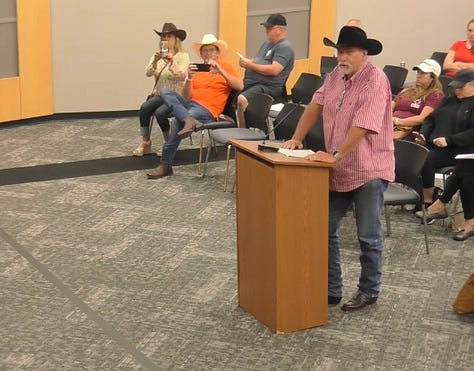

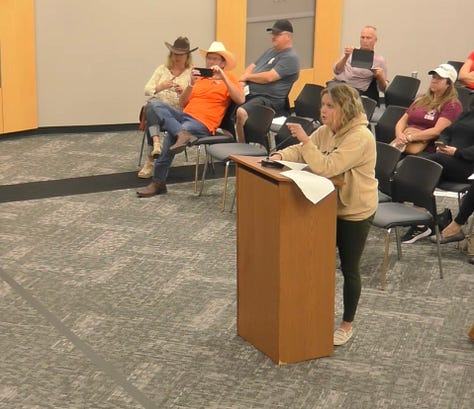

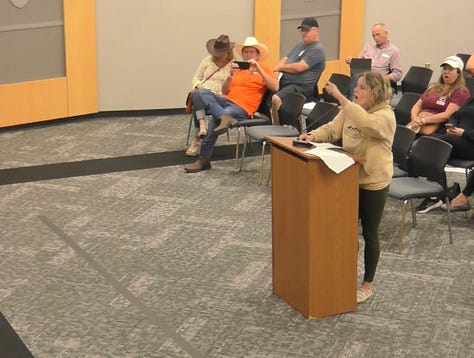

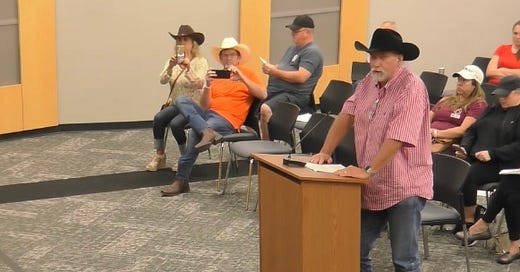

That meeting came after 37 of the challenged books were returned to library shelves by reconsideration committees following district procedures. In all, fifteen people spoke against books during public comment, the majority of them not residents of the district or parents of Plano ISD students. Ayres was there; so was CDF executive director Tara Schulte, who is also not a Plano resident. “Someone needs to be on these committees that has the values that are Biblical,” she said.

Kyle Sims, a North Texas social media personality who goes from district to district speaking about Satanists and “protecting the children” made an appearance, talking about brothels and massage parlors. So did Blaze TV host Sara Gonzales, who read a passage from Sarah J. Maas’s novel The Court of Mist and Fury like she was auditioning for Meg Ryan’s deli scene in When Harry Met Sally.

But the showstopper came when one of the few actual Plano ISD parents to speak started yelling at superintendent Theresa Williams. “Theresa, look at me!” she shouted. “You look at me! This is wrong! Look at my face!”

“You need to get off your high horse and do what parents want! Do you understand?” she concluded.

The spectacle apparently made more of an impression on district officials than May’s election results or the decisions made by the committees. Three days later, Williams sent a message to the district announcing that she and her leadership team would be reviewing all of the appealed book decisions, retraining district employees on evaluating books, and pausing all library book purchases. Shortly thereafter, the district website announced that 35 of the 37 committee decisions to retain books had been overturned. Those books included Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five, Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Half of a Yellow Sun, and Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, which collectively have appeared on the Advanced Placement Literature exam 12 times.

In emails to district staff, administration explained that their decisions were based on the need to “reflect the overall values of our community.”

“… it was determined that we needed to make adjustments to our processes.”

But the reversal of committee decisions, the removal of dozens of books, and the district’s new approach to evaluating library materials alarmed and angered some members of Plano ISD’s community.

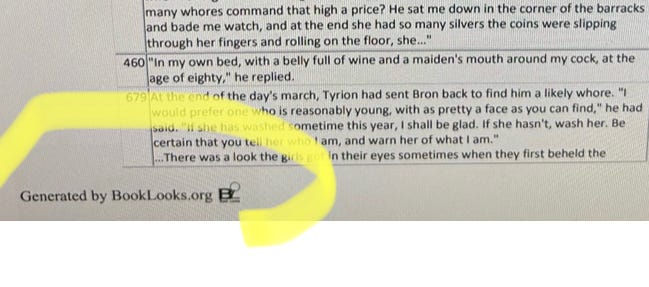

In a training on November 7, district librarians participated in a calibration activity meant to clarify the district’s stance on “what constitutes sexually explicit material in Plano ISD, and how this relates to library material selection.” During that activity, librarians were asked to read short passages from books and then rate that material according to a new “sexual content scoring crosswalk,” a 1-10 scale ranging from implied sexual activity to activity that may be “elaborately and graphically described, leaving nothing to the imagination.” Librarians then compared scores to check alignment.1

The excerpts used to complete the activity came from BookLooks.org, a website that promises to help users “find out what objectionable content may be in your child’s book before they do.” As Kelly Jensen first documented, BookLooks was created by members of Moms for Liberty, an SPLC-designated extremist group. It has been used to challenge and remove books in districts across the county. One analysis of book challenges nationwide found that nearly two-thirds came from books listed on BookLooks.2

But apart from the implications of using materials made by an extremist group, some members of the Plano ISD community worry that the district’s use of the BookLooks passages indicates an embrace of the Moms for Liberty approach to book evaluation: the idea that the value of a book can be determined by weighing only its most objectionable content, and not how that content is used or how it relates to the whole of the book. [Update, 11/18/23: The district has confirmed that it is now evaluating books based on excerpts, rather than the work as a whole. See below.]

It’s a view that goes against American jurisprudence, professional standards, and even HB900, the book removal law passed by the Texas legislature this year, which requires a vendor rating a book’s sexual explicitness to take into account “the full context in which the description, depiction, or portrayal, of sexual conduct appears, to the extent possible, recognizing that contextual determinations are necessarily highly fact-specific and require the consideration of contextual characteristics that may exacerbate or mitigate the effectiveness of the material.”

More to the point, it’s a view that seems to contradict the district’s own library materials policy and procedures, which have emphasized in a number of ways the importance of context for judging a book.3

Other Texas districts, including Keller, Katy, and McKinney, have moved to a rubric-based evaluation system in which it is no longer necessary to judge works as a whole before removing them. But all of those changes were made by the district board, within a system that allowed the public to review and comment on the policy change and required trustees to take a public vote.

Plano ISD, on the other hand, argued that it did not have to bring their evaluation process before the board because the changes “align with Board Policy and do not replace Board Policy.”

“… it does not mean we are not incredibly grateful for you …”

The changes did not appease the faction behind the book challenges. Instead, CDF and aligned parents returned to the next board meeting on November 8 with a longer list of demands. Among them, they asked for policy changes including the immediate removal of books challenged for sexual content and typed names and titles of any district employee who serves on a reconsideration committee. Schulte also asked for an audit of the district’s entire library collection.4

More troubling, the group demanded action against the teachers and librarians who served on the committees whose decisions had been overturned.

In an email sent Monday, the district assured those committee members that it was grateful for their efforts and that the process changes are “in no way meant to reflect negatively on the work of the reconsideration committees.” Those employees also received 3-6 hours of professional development credit as a gesture of appreciation for their work.

But members of CDF took the opposite message from the book removals, arguing they showed that committee members “have proven they cannot be trusted with the young, impressionable mind of a child.”

“CDF and parents are insisting on accountability for district employees who reviewed and approved explicit material for minors,” said Ayres at the November board meeting. “As your internal review confirmed, the individuals who served on these committees showed extremely poor judgment and should never again be allowed to serve in any capacity that requires the review of any content and [its] appropriateness for minors.”

One Plano educator who has served on review committees told me that she has little interest in private emails of support or tokens of appreciation for her work.5 “They threw all that away, let community members say horrible things about us without defending us, and then offered only three hours of credit when we’re required to get fifteen each year.”

“Their inability to go to bat for us, after we spend hours and hours doing free labor, is extra demoralizing,” she said.

…

Update, 11/18/23: A spokesperson for the district responded to a request for comment after this piece was published. Her statement said, in part:

District policies, guidelines and review processes are in place to ensure the educational suitability and age-appropriateness of materials while upholding all relevant laws and regulations. We would like to emphasize that the removal of certain books from our libraries was not taken lightly. Our primary goal is to create an inclusive and safe learning environment for all students, in compliance with all laws. The changes in our procedures do not override the provisions of Board Policy EFB (LEGAL and LOCAL), but are instead made in accordance with that policy. As such, Plano ISD does not remove titles because of the background of authors or characters, or simply because of the viewpoint expressed in the book. We share your belief that literature requires choice and representation. However, choice and representation for students can be achieved without including titles with sexually explicit content. The books that have been removed represent less than one-tenth of one percent of our library collection. We believe books are an essential part of school and individual learning, and we want all of our parents to feel comfortable with their students utilizing our libraries.

She also stated that reading a text in its entirety is no longer a required part of evaluating books in Plano ISD, writing that now “evaluative considerations can be based on excerpts, rather than a work as a whole, and also include the degree of explicitness as part of the evaluation.”

It’s not yet clear how the new “crosswalk” relates to the district’s overall book evaluation system. Nor is it clear who conducted the “internal reviews” that removed 35 books, or whether they read the books they removed in their entirety. I asked Superintendent Theresa Williams for clarification on these points, but she has not yet responded. [Update, 11/18/23: A spokesperson for the district responded after this piece was published. The reviews were conducted by “district staff.” She did not clarify whether or not the removed books were read in their entirety, but she did say that the process no longer requires it.] What is clear—based on an email that went out to book committee members on November 13, is that the “crosswalk” was at least part of a new procedure for reviewing that was applied to those books that were removed.

BookLooks can only make books look bad; it extracts nothing from books except potentially objectionable content, and doesn’t contain detailed summaries, reviews, or any information that would contextualize that content.

Current policy requires books to be removed if they are “obscene” or “harmful to minors,” terms that are clearly defined in law. Obscenity can only be determined if the work in question, “taken as a whole, lacks serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value.” The policy also references Island Trees School District v. Pico, in which the Supreme Court ruled that material may be removed from schools if it is “pervasively vulgar” or “educationally unsuitable.” Neither of those terms is as well-defined in the law as “obscene” or “harmful to minors,” but both suggest familiarity with a text in its entirety. Additionally, various procedures require a consideration of a book as a whole. The official reconsideration form, for example, informs potential book challengers that if they haven’t read the book in its entirety they should do so before completing the challenge.

Specifically, CDF demanded:

That parents always comprise a majority of any reconsideration committee.

The immediate removal of any book challenged for sexual content.

That committee always contain at least on elected board member.

A specified timeframe within which reconsideration decisions would be resolved.

Typed names and titles for each reconsideration committee member, “so that parents can know who is on each committee.”

The district employee asked not to be identified in this piece.

As a Plano ISD parent, what can we do to push back against this? It’s frustrating to see extremists cause this level of chaos.