Five Things on the Floor Discussion of HB900

(Or: Why you should watch Erin Zwiener's remarks)

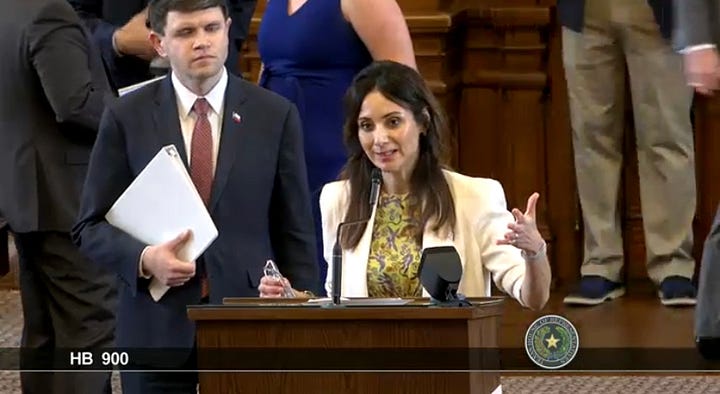

You’ve probably heard the disheartening news that the Texas House of Representatives passed HB900 this week. The bill, which now goes to the Senate, would require any vendor who sells books to a Texas school to rate those books in terms of their sexual content, with books that depict sex in a “patently offensive” way being totally banned from all school libraries, and access to other books that depict sex requiring parental permission.

I was teaching while the bill was on the floor (“It passed,” my wife texted me during 5th period), so I’ve been catching up on the debate after the fact. I intended this post to be a sort of summary of the high and low points, and I want to acknowledge the objections made by representatives Ron Reynolds, Jon Rosenthal, and Toni Rose—as well as the great work Gina Hinojosa and James Talarico did to highlight the bill’s unintended consequences. But if I had to distill the discussion to five points, five things you really should take away from what happened in the Texas House on Wednesday, three of those things would come from Erin Zwiener’s incisive remarks on the bill, and two would be unintentionally revealing comments made by the bill’s author, Representative Jared Patterson.

I’ll start with Representative Zwiener’s remarks, which you can find at 2:25:30 on this video. Watching them is bittersweet, like reading a killer dissent from Sonia Sotomayor on a crushing Supreme Court decision. But you should still watch them, because Zwiener got to the heart of the issues behind the pro-censorship movement. Here’s why:

Zwiener called attention to the role that the theme of sexual violence plays in determining which books get challenged and which don’t. “When I watched the layout of this bill in the House Public Education Committee,” she said, “over and over again the scenes people read from books as being ‘too explicit’ to possibly be in the hands of our teens were scenes of sexual assault.”

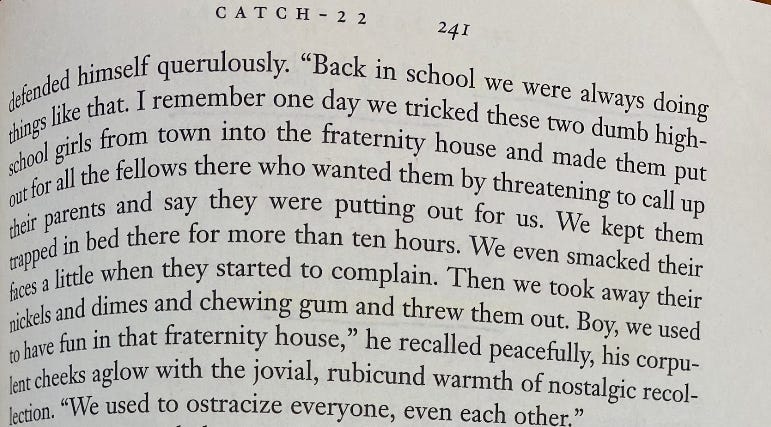

This is what I was talking about in my last paid post. To be a little more precise, it’s not just scenes of sexual assault that rile up the book banners. After all, Rep. Patterson hasn’t challenged The Fountainhead or Catch-22 in his home district, Frisco ISD.

No, what bothers Patterson and book banners throughout Texas are scenes of sexual assault that are written from or sympathize with the victim’s perspective. As Zwiener noted: “It was the scene from The Bluest Eye. It was the scene of sexual assault in The Perks of Being a Wallflower.”

Those books are important because, rather than normalize, excuse, or even glorify rape culture, they give young readers the words to challenge it. Zwiener bravely described a sexual assault she experienced as a seventeen-year-old, and said at the time she “didn’t have the words” to call that experience rape. “I could have used a book about sexual assault to help me define what had happened to me.”

Zwiener called out the book-banning movement’s bait-and-switch. Zwiener said, “This bill was drummed up using images primarily from books that use images to try and talk about sex education. And I think we can all agree books that are trying to deal with sex education, whether from a perspective we agree with or a perspective we disagree with, are very, very different from narratives—narratives that we use to understand the world around us, narratives that we use to develop empathy, narratives that we use to cope with what has happened to us in our lives.”

If you’ve written publicly about the value of the novels like The Bluest Eye or the The Perks of Being a Wallflower, you’ve likely been spammed in the comments with images from sex ed books which, obviously, are going to be franker and more graphic than literary memoirs or novels, which serve an entirely different purpose, and which should be discussed and debated on different terms. But the book-banning movement depends on conflation—conflating sex ed books with novels and memoirs, conflating books meant for older teens with books meant for “children,” conflating LGBTQ themes with sexual explicitness. It’s how you use Gender Queer to ban Drama, and how you generate lists of dozens, sometimes hundreds of books that you can, in turn, use to build outrage for political ends. “Hey, there’s a sex ed book in our school library that might be too advanced for students,” doesn’t generate the same heat as saying, “Here’s a list of hundreds of pornographic books in our libraries,” which is how I’ve seen people describe the Elliotts’ book list in McKinney and the Matt Krause list.

Finally, Zwiener made the connection EVERYONE needs to see: Zwiener’s mic-drop moment came next, when she said, “This bill did not start with HB900 and Representative Patterson’s conversations with Frisco ISD about books upon their shelves. This bill started with House Bill 3979, that was directly targeting the narratives of people of color about race and racism.”

If you think “critical race theory” was last year’s rightwing anti-book crusade and “porn in schools” is this year’s, you’re missing the point. These attacks are all tied together. That’s why just last week I was writing about Spring Branch ISD restricting Frederick Joseph’s The Black Friend under the vague notion of “educational suitability,” a phrase that appears in HB900 and that Zwiener and Talarico rightly questioned on the House floor.

It’s why the “pornographic books” that almost got the Llano Public Library closed this month included Isabel Wilkerson’s Caste.

And it’s why, in the committee hearing for this bill—which Patterson repeatedly said only targets books with sexual content—Representative Matt Schaefer angrily grilled the superintendent of Frisco ISD about whether his district’s libraries still possess any books from the Krause list. As Zwiener pointed out, that list includes hundreds of books that have no sexual content at all—Caste, Between the World and Me, The New Jim Crow among them.

As Zwiener put it, “I think that is something we need to fundamentally understand about this legislation: it is not about protecting kids. It is about allowing books to be discriminated against in our schools because we disagree with the content within them or with the types of narrative they’re sharing.”

On the other end of the floor, Representative Patterson made a few comments in defense of the bill that were incredibly revealing. Here are two:

Patterson compared the bill to “protections” the legislature has put in place regarding sex ed. He said, “I think we also have to have an added layer of protection just as we have in our sex ed curriculum in public schools, we needed another layer of protection in our public school libraries.”

If you haven’t been following Texas education law recently, you might not know what has happened to sex ed in the state. Even though overwhelming majorities believe students should learn about reproductive health and sexual wellness in school, sex ed is not required in Texas. In 2021, the legislature made sex ed an opt-in feature of K-12 schooling—in order to participate in sex ed, students must turn in a permission form signed by their parents. As a result, sex ed programs in some schools have cratered.

Here’s what that looks like in the school where I teach: Before the law passed, basically all of our 12th-graders received sex ed. Since the law passed, participation rates have plummeted. It’s not that our students’ parents are forbidding them from taking the class, either. It’s just that things happen when you have to turn in a permission form. The form gets lost; the form gets forgotten. Students decide they’d rather have a study hall instead of another, non-required class. The last two school years, we’ve had 20% - 25% of our seniors participate in the program.

So when Patterson says he wants library use to look like sex ed in the state, pay attention! Because sex ed in Texas has been decimated in the past two years.

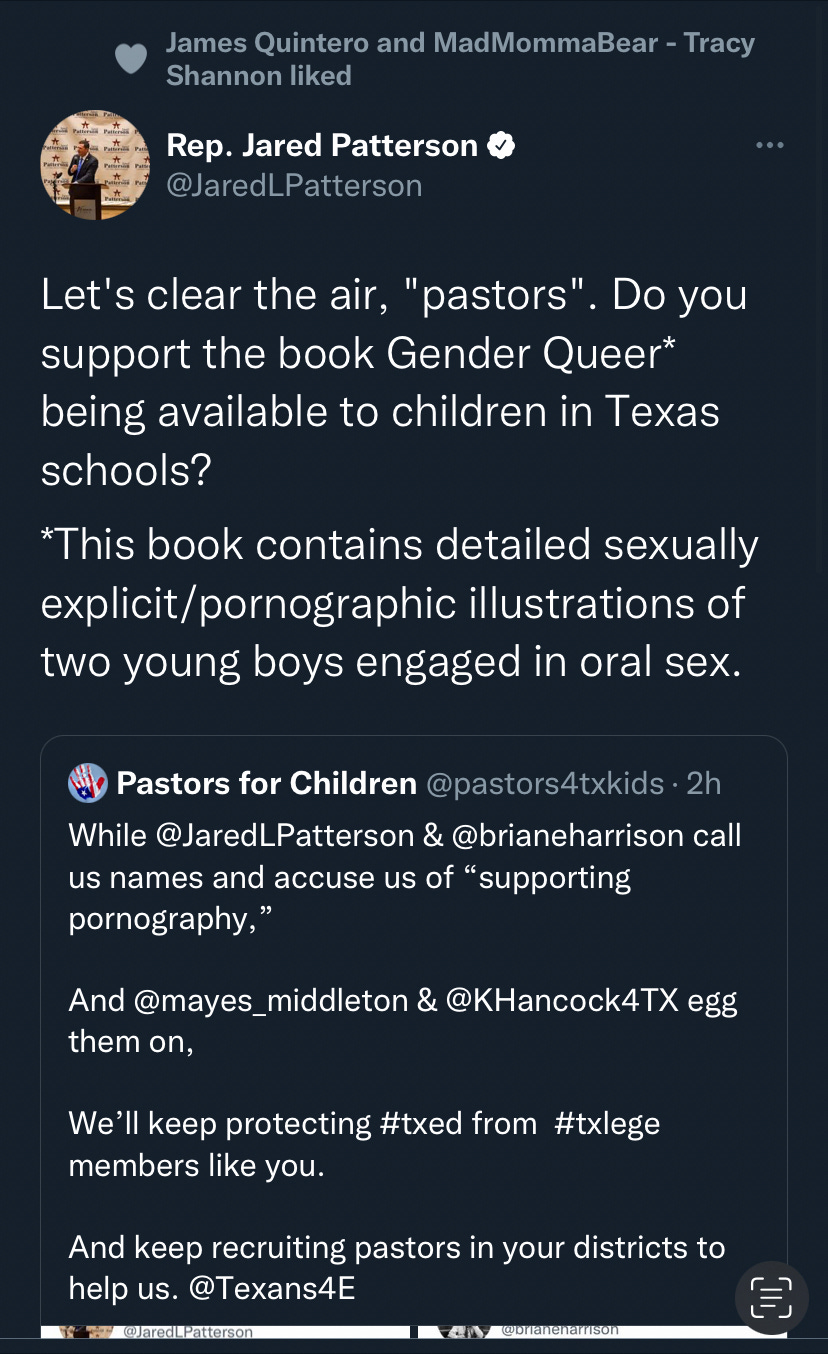

Patterson has been fighting for eighteen months against a book he hasn’t read. Another revealing moment came when Talarico pushed Patterson for an example of a books that would be considered “sexually relevant” and “sexually explicit” under the bill. He couldn’t come up with an example of a “sexually relevant” book, but for a “sexually explicit” book he named Maia Kobabe’s Gender Queer, which, he said, “graphically illustrates two boys engaged in some activities.”

That’s something he’s said before. In fact, he’s been more specific, writing that the book “contains detailed sexually explicit/pornographic illustrations of two young boys engaged in oral sex.”

If you’ve read Gender Queer, you know that’s not true. The book is a memoir in graphic novel form; the author is non-binary, has identified as asexual and was assigned female at birth. In the scene in question, the author is an adult, in grad school, in a relationship with a cisgender woman. And while the scene is graphic, and it is fair to question whether it’s appropriate for schools, it’s not pornographic. In fact, it describes a disappointing sexual experience, which I’m fairly certain makes it the opposite of porn.

Those are not small details. The author’s navigation of gender identity is the central theme of the book. It’s right in the title! And yet Patterson called Gender Queer “the book that kind of started this whole thing.” He also said he’s been working on HB900 for eighteen months.

In all that time he apparently never actually sat down and read the book.

How emblematic is it that?

I spent far too much time and at the same time not enough diving into all of this this week. It didn’t take me long to realize they never read the books. Which makes me question why they are even bothering to go so hard on something they don’t read, other than to advance other agendas that work alongside this. What’s worse, is how manipulative they are to mommy groups and the lengths they go to lie.

Thanks for your analysis.