The two women sit across from each other at a sidewalk cafe table in Los Angeles, their hair loose and center-parted, their cell phones in front of them. Each is recording the interview—both say—to defend against the possibility that the other might release unflattering bits out of context.

On the left, closest to the street, is journalist Taylor Lorenz, who is writing a story about the woman on the right, Chaya Raichik, for the Washington Post. Raichik also calls herself a journalist; her work consists of scrolling social media for potentially embarrassing clips of supposed liberals (often LGBTQ individuals) and then framing and amplifying those clips for ridicule by the massive conservative audience that follows her Twitter account, Libs of TikTok. The targets of her posts often face violent threats; as Lorenz points out in the interview, 33 institutions—schools, hospitals—have received bomb threats after Raichik has posted about them.1 The specific occasion of this interview is the death in Oklahoma of a non-binary student who was bullied for months in a district where Raichik targeted a teacher and where at least one trans student claims to have been “bullied by people who watch Libs of TikTok.”

For the interview, Raichik wears a t-shirt with an image of Lorenz crying during a TV interview about the online abuse she’s faced. It’s internet trolling brought into the real world—every time Lorenz looks across the table, she’s faced with her own image in a moment of abjection. Raichik wants to trap Lorenz in a horrifying hall of mirrors, an image of herself humiliating herself forever.

At least that’s the idea. In reality, Lorenz is unfazed by the t-shirt troll. In the hourlong interview—which Lorenz released in full after the Post published her story—Lorenz asks thoughtful, probing questions that Raichik struggles to answer. Lorenz pushes back when Raichik deflects, gently points out inconsistencies and contradictions. When Raichik tries to turn the tables and question her interviewer, Lorenz obliges, pausing to think about her answers and admitting when she doesn’t know how to respond. Where Lorenz comes off as generous and reasonable, Raichik seems defensive and petulant and, well, like she hasn’t really thought through the positions that have made her a right-wing media force.

“ohhhh Chaya Raichik is, like, STUPID stupid” went one tweet that echoed a popular reaction after Lorenz released the video. But I don’t think that’s fair. It’s easy to sound inarticulate when you haven’t prepared for an interview. What the interview does reveal is the extent to which Raichik, like so much of the right-wing counter-world that has developed in recent decades, apes mainstream institutions, exploiting their missteps rather than developing a thoughtful framework of ideas.

Every time Raichik managed a response in Lorenz’s interview, it took the form of whataboutism. When Lorenz asked how Raichik feels about the violent threats the subjects of her posts receive, Raichik countered, “I got tons of death threats this week after the entire media machine came after me. So are they responsible for those?”2 And when Lorenz asked why Raichik spreads disinformation (her Twitter account still includes a tweet suggesting falsely that the Uvalde school shooter was trans), Raichik argued that the mainstream media lies, too.

It’s not that Raichik doesn’t have a thought in her head—it’s just that all of her talent is bent towards making herself invulnerable to attacks by drawing equivalences to the people (and groups, and institutions) she wants to bring down.

I watched Lorenz’s interview with Raichik, coincidentally, on the same day I finished reading Naomi Klein’s newest book, Doppelganger: A Trip Into the Mirror World. Doppelganger is ostensibly about a situation that’s very specific to Klein: the way she is continually confused with Naomi Wolf, a different writer and public thinker who tackles some of the same topics as Klein but takes some wild—and problematic—positions on those topics. But, really, Doppelganger is about the way any of us can lose our mind in a world that’s deliberately flooded with misinformation, gaslighting, and confusion.

Lots of people have noted that America now seems divided into two realities: two media ecosystems, two social media bubbles, two sets of beliefs about COVID, the 2020 election, January 6th, Black Lives Matter, “indoctrination” in schools. Klein details how much one of those worlds feeds off the other, simultaneously drawing authority from its similarities with the original while seeking to undercut the original’s authority.

Klein gives a dozen examples, but you probably already have a few already in your head. For me, it’s the American College of Pediatricians, a crank group designed to be confused with the American Academy of Pediatrics while offering diametrically opposed opinions on culture-war issues like LGBTQ rights or trans-affirming medical care. Every time I see those opinions filtered up to “investigative journalists” at propaganda outlets (themselves meant to look like real news sources), I scream into my fist.

I remember, growing up, that virtually every cartoon or superhero show I watched had an episode where the hero faced their double, and there was always a moment when you couldn’t tell which was which, who was good and who was bad. Or an episode where the hero became his own evil twin, a bump on the head or an evil potion making him behave in ways opposite to his normal behavior, while he looked the same as always. Those episodes always made me profoundly uncomfortable. Doppelganger dissects exactly why: if that double is bad, and they’re like my hero, what does that say about my hero?

Klein’s exasperation at being confused for Naomi Wolf is a great vehicle for capturing the feeling of living now, of watching this mirror world take shape and grow. Reading Doppelganger, I sometimes felt the same rising heartbeat, the same constriction of my throat, that I get when I open Twitter or watch the news.

What’s more, Klein details the way that anxiety compounds as you watch the mirror world increasingly intrude on reality. Because all of this mimicry, all of this nonsense, isn’t a game. I know, for example, that when Greg Abbott—fed on (and feeding) the mirror-world obsession with immigrants—talks about barring undocumented students from public schools, he’s talking about my students; and when right-wing media figures talk about going after teacher’s certificates for distributing “porn” in schools, they mean going after me for assigning books like The Glass Castle or Salvage the Bones.

And Klein wrestles with the question we all face as we look at the mirror world: what to do? What do we do when the most careful fact-check, the most brilliant deconstruction or pithy takedown does nothing to stop the mirror world’s growth—or maybe worse than nothing, because it strengthens the other side’s resolve and deepens their hatred of people like us?

It’s a paralyzing feeling.

And paralysis is exactly the point. Doppelganger shows that the mirror world exists in order to make it impossible to do real work in the real world—whether that be alerting the public to the dangers of climate change, fighting racism or homophobia, or challenging censorship.3 It does that not by attacking the work itself, but by paralyzing you, by making you unsure of yourself and by making your potential audience think that they don’t have to listen to you.

And it does that by offering up a distorted reflection of you—all surface, no depth or context. A still image from a video of you, laser-printed on a t-shirt, staring back at you while you try to do your work.

How do we respond?

Doppelganger isn’t a self-help text or organizer’s manual, but from my reading of the book, I distilled three strategies for resisting the crazy-making powers of the mirror world:

Lose your self-importance. When you find yourself face-to-face with the mirror world—especially when the mirror world reaches into your world and attacks you—it’s normal to respond by performing your own identity even harder, as a means to assert your own reality. But Klein suggests a model of “unselfing” (the term comes from Iris Murdoch) that she likens to the Buddhist concept of ego death. Laugh at yourself. Connect with others. Let your doppelgangers teach you “we are not as separate from one another as we might think” (326).

Don’t respond in kind. Denizens of the mirror world attack their targets’ credibility with wild personal accusations. Often, those accusations are pure projection. It can be tempting, then, to try to end the argument by striking back with a counteraccusation. To yell when they yell, point when they point. But that’s a trap that only ends in escalation. Instead, Klein says (citing john a. powell), we should be hard on structures, not people. That is, we should never feel bad about being critical towards the ideas and systems that are mucking up our world, but we certainly can’t challenge those if we’re attacking the person across a computer screen from us. Much better, Klein says, to “reach toward many different forms of possible connection and kin, toward anyone who shares a desire to confront the forces of annihilation and extermination and their mindsets of purity and perfection” (330).

And all of this is only possible if we can learn to calm the fuck down. Klein repeats a phrase she took from John Berger: “Calm is a form of resistance.” She explains:

“Calm is not a replacement for righteous anger or fury at injustice, both of which are powerful drivers for necessary change. But calm is the precondition for focus, for the capacity to prioritize. … Berger helped me to see that the search for calm is why I write: to tame the chaos in my surroundings, in my own mind, and—I hope—in the minds of my readers as well. The information is almost always distressing and, to many, shocking—but in my view, the goal should never be to put readers into a state of shock. It should be to pull them out of it” (227).

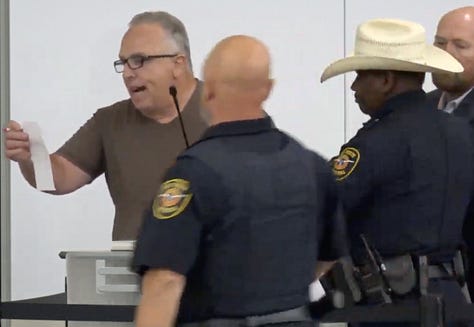

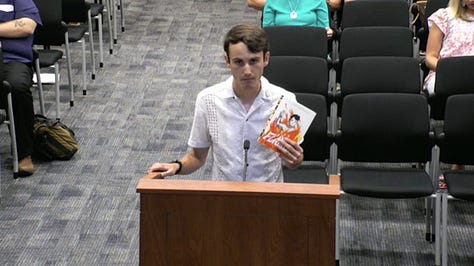

It’s easy to see how these lessons translate to book-banning battles. Shock is the book banners’ primary tactic. That’s the point of the images, the paragraphs out of context, the angry recitations at board meetings. Their goal, too often realized, is to provoke action without thought or perspective.

I’ve always known that I write to tame the chaos (first) in my own mind and (second, hopefully) in my readers’. I’m starting to realize that another worthwhile goal in this work is to pull some part of our culture out of a state of shock.

That’s what made Lorenz’s interview with Raichik so compelling. While the lessons Klein doles out in Doppelganger can seem airy and abstract, Lorenz gave us a concrete example of what they look like in practice. In the interview, the impeccably prepared Lorenz maintained her calm, and that allowed her to avoid taking Raichik’s bait, to point out shared experiences rather than drawing hard lines, to laugh off (graciously) Raichik’s obvious provocations. If Lorenz had taken herself too seriously, even the t-shirt troll might have worked. Instead, the interview exposed Raichik’s meager thinking, and even folks on Raichik’s side of the mirror admitted it didn’t look good.

Will Taylor Lorenz’s interview with Chaya Raichik bring down Libs of TikTok and shatter mirror world? Will it make our lived reality better? Not by itself. But it can be a model, a way to move towards a world that’s marginally less awash in projection and bullshit. Klein’s Doppelganger explains why.

This month, the pattern repeated in Northwest ISD in Texas, where local activists targeted a middle school teacher for weeks. After Libs of TikTok covered the “story,” bomb threats (determined to be a hoax) were sent to both the school and the teacher, using her home address.

It’s worth watching this four-minute exchange (21:03 - 25:00) in its entirety. Instead of being combative, Lorenz connects with Raichik by pointing out that she, too, receives death threats when her name shows up in Fox News. At the same time, she draws a distinction between the two of them, as public figures, and the teachers, students, and regular people Raichik holds up to mass scrutiny. And, again, even though she’s the interviewer, she responds to Raichik’s questions with goodwill and honesty.

Reading Doppelganger I kept thinking about Toni Morrison’s formulation of what racism does: “The function, the very serious function of racism is distraction. It keeps you from doing your work. It keeps you explaining, over and over again, your reason for being.”