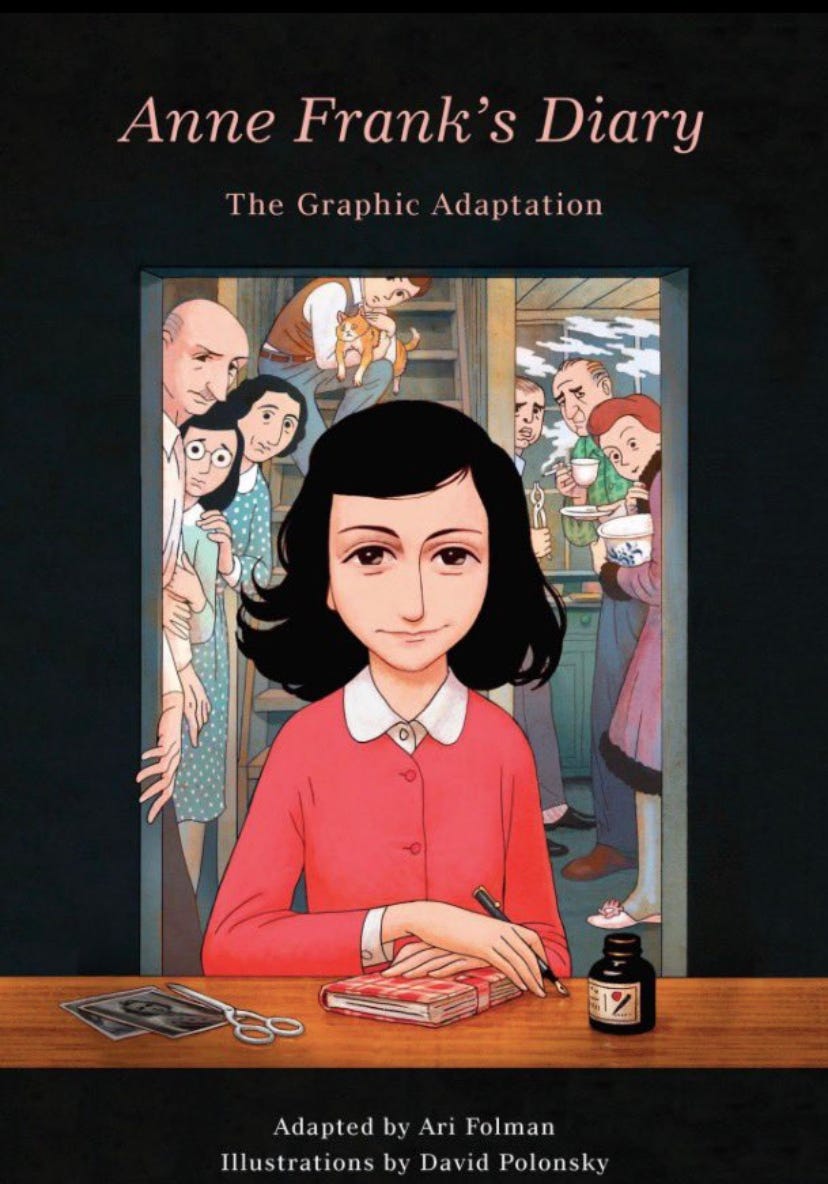

I’ve been accused on social media of writing too much about recent attempts to ban from schools Ari Folman’s graphic adaptation of Anne Frank’s diary. To be precise, one Texas book banner said I only focus on this one book when I talk about censorship.

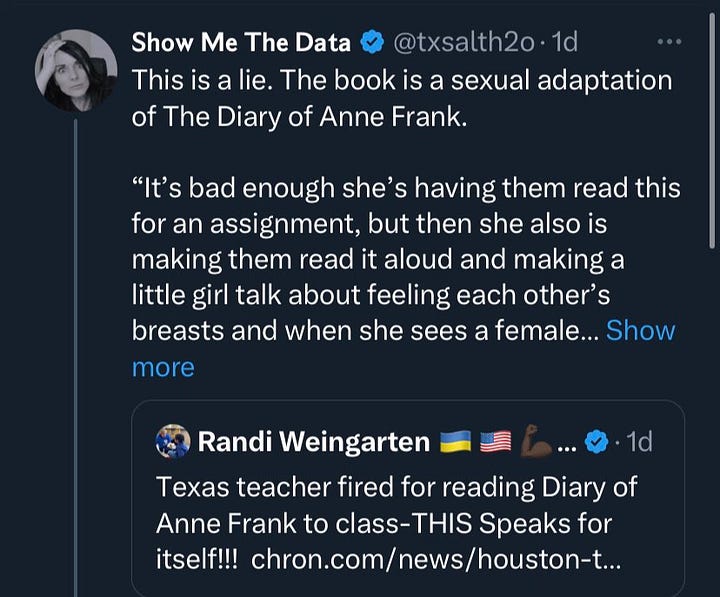

That’s obviously false—look around this Substack.1 But it is fair to say I’ve been writing about Anne Frank a lot lately on social media. In my defense, controversy about this book keeps popping up. First it was in Keller ISD, where the book was challenged in early 2022 and then (briefly) removed that August.2 Then it appeared on Republican operative Christin Bentley’s ever-growing list of “sexually explicit, pervasively vulgar, and educationally unsuitable” books, a list that has been championed by right-wing media personalities and has influenced district decisions around the state. Most recently Hamshire-Fannett ISD courted national outrage after a teacher in the district was fired for assigning the book to her 8th-grade students.

The controversy over the book is also irresistible because it’s a microcosm of the larger debate over books in schools. Here’s why:

Bans of this version of the diary are fed by ignorance. As NBC reporter Ben Collins realized recently, a big part of why the graphic adaptation has been banned from schools is that some people think that “graphic novel” means graphic (i.e., sexually explicit or violent) depictions of the events in the diary. They simply don’t know what the phrase “graphic novel” means.

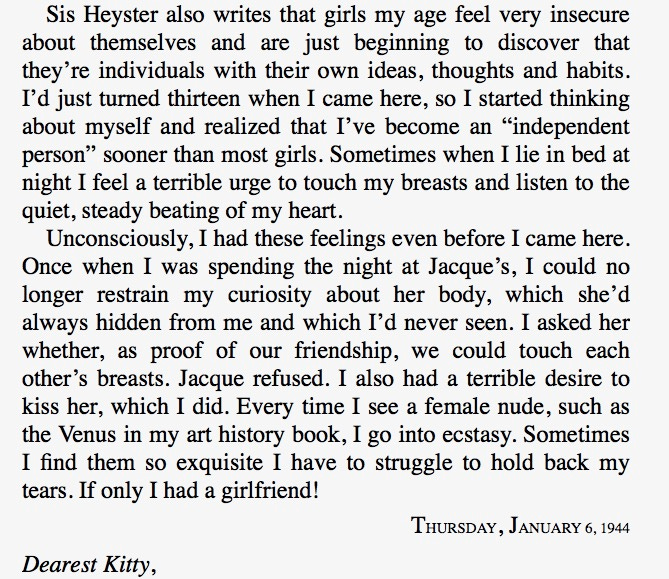

What’s more, people don’t know what’s in the diary itself. One right-wing “anti-woke” social media personality (with 82,000 followers) was shocked to learn that the graphic adaptation includes a scene in which Anne tries to kiss and touch the breasts of another girl at a sleepover—apparently not realizing that scene comes directly from the diary and has appeared in every major printed version in English, dating back to its first translation in 1952.

The generous interpretation is that these book banners have forgotten what they read in 7th or 8th grade. It has been a while for most of them, after all. The other interpretation is they never read the book in the first place. I’ve long suspected that our educational policy is being set by people who didn’t do their English homework back in school, so that tracks.

The bans also tap into anti-LGBTQ fervor. While Anne Frank wrote several potentially objectionable things in her diary, it should not escape notice that the one gaining the most attention is the one in which she expresses same-sex desire.

Finally, the controversy highlights the rightward stampede of our cultural wars, and the speed at which something that was once unimaginable can become the right’s entrenched position. When the book was first removed in Keller, local activists tried to paint its challenge as a false flag challenge made by “bad actors” in an attempt to make book banners look bad. But by the time the teacher was fired in Hamshire-Fannett ISD, cultural warriors had convinced themselves that the graphic adaptation is a “sexualized” version of the diary, not fit for minors.

It’s the perfect storm: people don’t know what’s in Anne Frank’s diary; they hear that there’s a “graphic” version of it and don’t know what that means; they see a page that taps into what book banners have been telling them about sexual content and LGBTQ indoctrination. Finally, because they’ve been primed to believe the worst, they launch misinterpretations on top of misunderstandings based on partial information taken out of context and presented deceptively.

Another way to put it: the graphic adaptation of Anne Frank’s diary has been given the Gender Queer treatment.

How are they justifying their censorship? Well, they start by saying the Folman version is a “sexualized version” or a “sexual adaptation” of Anne Frank’s diary. It’s not. As I’ve detailed repeatedly on Twitter, Folman’s adaptation is a tasteful representation of the whole of Anne’s diary. Yes, he includes the parts where she wrote her thoughts and questions about sex, but all of those parts were written by Anne herself, and included in the definitive version of the diary that has been in school libraries for decades. And again, the most controversial part has been included in every single major American translation of the diary. Any of us who read the book in school read that passage. And Folman handles those passages with sensitivity.

When you point this out, the banners turn to a more abstract argument. It’s not the real diary, they say.3 Folman “added scenes,” they say. They’re protecting the book, they say. I’ve even seen them citing this critical 2018 review in the Atlantic, which objects to Folman’s adaptation for reasons having nothing to do with its sexual content.

Sigh. Look, the textual history of Anne Frank’s diary is complex, and it’s hard to say what is actually the “real” diary. We know that Anne started writing in a cloth-bound book she was given when she turned 13 and that her writing soon exceeded the pages of that volume. We know she continued writing in other notebooks and loose-leaf pages. We know that she heard a call on the radio for citizens to record their lives during the war, and that—now with an eye towards publication—she went back, revised some of those entries, filled in details after the fact, and removed sections and passages. We know that her family’s ally, Miep Gies, found her diary scattered in the annex where they hid, and that after the war, her father put together and published a version of the diary that became what most of us know as “the Diary of Anne Frank.” We know that scholars have continued to compare and contrast different versions of the diary—and even find previously unknown entries—for seventy-five years.4

Like I said, it’s complicated! Fortunately, we can call the book banners’ textual argument what it is: A smokescreen.

A parent in Hamshire-Fannett ISD defended the firing of the teacher who assigned Folman’s adaption by saying, “It’s bad enough she’s having them read this for an assignment, but then she also is making them read it aloud and making a little girl talk about feeling each other’s breasts and when she sees a female she goes into ecstasy, that’s not OK.”

Y’all.

That parent doesn’t care about textual history. She doesn’t care if her kids are reading from the graphic adaptation or the 1952 American version or a leather-bound facsimile of Anne’s handwritten pages. She doesn’t care if her kids teach themselves Dutch to read the diary in its original language. She cares about one thing: her kids are reading about breasts and girls kissing.

So, dispensing with the textual argument, we can talk about what this is really about. And maybe this is unwise, and maybe it will be fruitless, but I want to address that parent, and Sarah Fields, and Christin Bentley, and all the other parents who are afraid of this book getting into the hands of young people. I say this with sympathy, as the father of a teenager:

The passages you’re objecting to have sometimes been edited out of published versions of Anne Frank’s diary. But they weren’t added in or made up out of whole cloth. Not by an editor, not by some “woke” educator. Anne Frank wrote them. Let me say that again: Anne Frank. An adolescent girl.

In other words, if you don’t want your kid to read them, you’re saying you don’t trust your teenager with the diary of another teenager. Specifically, the diary of the sensitive, observant, good teenager named Anne Frank, who happened to be witness to and victim of one of history’s most terrifying atrocities.

You’re saying you’re worried that Anne Frank will be a bad influence on your child.

You’re scared of Anne Frank.

Except maybe that’s not even it. Maybe the real issue is that Anne Frank was a teenager like your kids are (or will be) teenagers. Your kids have (or will have) thoughts like the ones Anne Frank wrote down. Maybe that’s what this is really about.

And that’s why I say this case is so illustrative. Because the fear that drives your attacks on the graphic adaptation of Anne Frank’s diary is the same fear that drives the uproar against Gender Queer and All Boys Aren’t Blue and The Perks of Being a Wallflower.

This case just shows how profoundly that fear has affected your common sense. It doesn’t matter how tame the thoughts, how modestly expressed, how little they have to do with a book’s message, or how important that message is.

Your kids are growing up, and that scares you.

By the way, stay tuned for a project I’ve been working on involving All Boys Aren’t Blue.

I was one of the first people outside of the district writing about this challenge. The initial challenge in Keller ISD is what prompted me to read Folman’s adaptation.

There’s a whole essay to be written about book banners’ tendency to go after graphic novel versions of classic texts, and how that tactic allows them to attack important ideas and make them harder to access while still offering the cover of “we’re not going after the real …” It’s happened (with less public notice) to Brave New World and The Handmaid’s Tale, too.

Two writers to read on this topic are Francine Prose, whose engaging Anne Frank: The Book, the Life, the Afterlife (2009) details this complicated history, and Ruth Franklin, who is writing a book on Anne Frank and who challenges the conventional view that Otto Frank unduly censored his daughter’s writings.

"I’ve long suspected that our educational policy is being set by people who didn’t do their English homework back in school, so that tracks." - Absolutely I think this is a huge part of it, especially for some of the people showing up at school board meetings. I do think people like Bentley are at least extremely cunning and knowledgeable about what they are doing. And I sometimes wonder if they even believe themselves in what they are saying.

And thanks for Bentley's new Substack link. I knew she had stopped posting at her other one but I deleted Twitter so I was no longer up to date on where she's writing now.