McKinney ISD Changes Its Definition of Obscenity

My second Substack post was supposed to be a preview of McKinney ISD’s upcoming trustee race, in which a “hate slate” of book banners and anti-LGBTQ candidates has already coalesced to try to flip the school board. But that post has been superseded by big news out of this week’s school board meeting, news that reflects yet another trend in book banning in Texas.

On Wednesday night, McKinney’s board of trustees voted unanimously to institute changes to its policy on library materials that will make it easier to get books removed and could result in McKinney students losing school access to quality literature. Board members presented the changes as clarifications meant to help librarians and principals, but the revisions are dramatic.

There were two significant updates to the district’s policy EFB Local, which details what materials can be made available to students in school libraries in McKinney. First, the new policy removes a requirement that reconsideration committees consider the text “as a whole” when evaluating a book for obscenity. The update means that a book can be challenged and removed on the basis of a page or a paragraph, no matter the value of the work as a whole or how that passage fits into the context of the work. As board member Stephanie O’Dell put it, “If a parent comes and says page 5, 9, 27, whatever, then the librarian and principal have the authority to go, ‘Okay.’”

The second change, which board members framed as clarifying and elaborating the definition of obscenity, included some language from Texas Penal Code statute 43.21, which in part identifies “obscene” material as that which depicts or describes “patently offensive representations or descriptions of ultimate sexual acts, normal or perverted, actual or simulated, including sexual intercourse, sodomy, sexual bestiality; or patently offensive representations or descriptions of masturbation, excretory functions, sadism, masochism, lewd exhibition of the genitals, the male or female genitals in a state of sexual stimulation or arousal, covered male genitals in a discernibly turgid state or a device designed and marketed as useful primarily for the stimulation of the human genital organs.”

Notably, the new policy does not include all of the Texas Penal Code’s definition of obscenity, which also insists that material be judged “as a whole,” and requires that objectionable material be weighed against a work’s “serious literary, artistic, political, and scientific value.” The two changes, of course, are related: you can’t judge a work’s literary value if you don’t read the whole thing.

The Board’s Rationale

In conversations over the phone and via email, Board President Amy Dankel confirmed that a work’s literary value will no longer be considered in the reconsideration process for library materials, and said, “We want every student to be able to see themselves and others who are different than themselves in amazing literature. We truly believe this is possible while avoiding ‘descriptions of sexual acts.’”

She also emphasized that the new policy only applies to library books and should not affect classroom materials. This is especially important for Advanced Placement classes, she said, because “many of the books in question are Advanced Placement class books, [and] these are books of literary, artistic, political and scientific value.” Dankel also clarified that non-AP teachers would have similar leeway and support from the board. The board’s rationale, according to Dankel, is that the district trusts its highly trained teachers to guide students through challenging material, but they don’t want students encountering potentially objectionable books on their own.

When I expressed skepticism that parents who demand The Bluest Eye be removed from libraries would be okay with their kids bringing the book home as assigned reading, Dankel acknowledged my concern, but pointed to the district’s record of supporting teachers’ instructional choices.

Potential Consequences

But Dankel candidly acknowledged that MISD’s new policy may result in the removal of books that otherwise would have been available to McKinney students. “I think my biggest worry with this,” she said, “is that only students whose parents could afford to buy them books would have a broad range of books to read.”

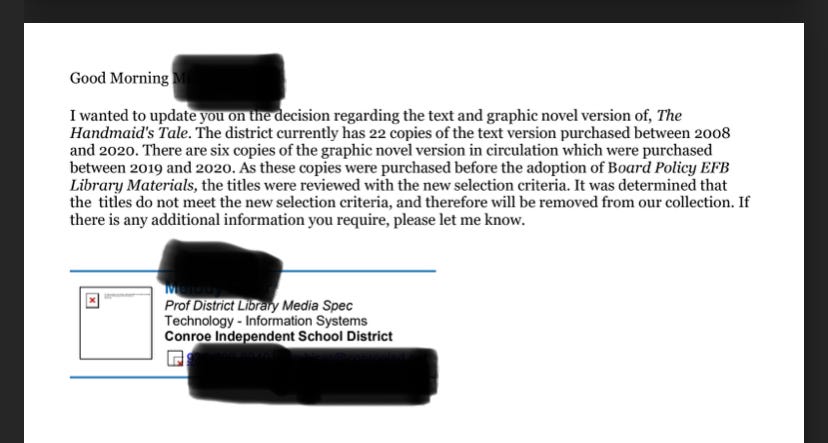

That has been the result in other districts that have adopted similar policies. Last fall, neighboring Frisco ISD implemented a library policy that used (and omitted) the same parts of the Texas Penal Code as McKinney. The FISD board subsequently voted to remove several books from the district that had survived challenges, specifically citing the new policy as they did so. And in Conroe ISD librarians removed The Handmaid’s Tale from district libraries before the book ever went through a formal challenge process—also pointing to new district policy as justification.

At Wednesday’s meeting in McKinney, the board’s decision to remove the “as a whole” requirement was met with applause from audience members, some of whom had come to the meeting to perform the now-familiar ritual of angrily reading out-of-context passages from books in attempts to shame the board into, well, making it easier to remove books based on out-of-context passages.

The move was also applauded online by Rachel Elliott, who earlier this year attempted to get 282 books removed en masse and is now running for a seat on the board. Board member Chad Green, whom the board censured this year in part for his conduct at a rally calling for books to be removed from the district, said, “This is a great change and it’s been long coming, so I’d like to congratulate the board for stepping forward and doing this.”

A Growing Trend

Judging books by individual passages, rather than works as a whole, is an unfortunate new trend in Texas school districts. Green, Elliott, and their allies across the state have watched in frustration over the past year as reconsideration committees have returned challenged books to library shelves, often noting the works’ literary value. The simple fact is that “descriptions of sexual acts” are fairly common in valuable literature—from Chaucer to Hemingway to Toni Morrison and Alice Walker—including books that have been standard high school fare for decades. While activists have sought to portray such works as “obscene” or “harmful to minors”—and thus demonize teachers and librarians as groomers and pedophiles—they’ve run up against the language of the law, and against committees who have done their diligence and read the books in full.

To get around the law’s language, pro-censorship activists have taken two main tacks: some have argued for book-rating systems, like the one Keller ISD adopted last summer, which delineate what specific content can appear in books at the elementary, middle, and high school level, and what content is forbidden from district library books. Others have pushed their districts to do exactly what McKinney’s trustees—and Frisco’s and Conroe’s boards before them—have done: excise from district policy the parts of the law that make removing books difficult.

The Result of Mass Challenges

So it’s easy to see why McKinney’s book-banning faction celebrated Wednesday’s decision. What’s harder to understand is why the district’s board voted for the measure. McKinney’s board is not a group of extremists; in fact, the board has stood firm for the past year in the face of relentless, vocal pressure to remove books. In the race preview I was going to publish before this news broke, I was planning to praise the board incumbents for their insistence on building an inclusive district, and for their support of teachers and librarians.

And that’s how they explained their decision. “I believe this helps support our teachers and administrators at the local level, the campus level, because it provides them a rules of the road so that they can make decisions at the local level and feel like they have the backing of MISD board,” said trustee Phillip Hassler on Wednesday. Dankel described the new guidelines as “fair and clear,” and pointed out that district administration had specifically asked for a clearer policy, as committees were coming to split decisions on book reconsiderations.

But that doesn’t mean the extremists’ efforts didn’t have an effect. In our conversation, Dankel told me the need for clear-cut criteria came as a result of the mass of books challenges winding through the system, and the time those challenges were taking away from educators’ work. In other words, a minority faction in McKinney ISD was able to win a significant policy victory by making it harder for educators to do their jobs. The result could be decisions that limit students’ learning.

Hi! I’m the one who brought up the connection to AP texts in the public comments portion of the meeting. I had hoped it would help them establish some reasonable standards of judgment wrt book criteria, but now I fear of pressing the issue too far and actually inciting the extremists to come after AP texts. (I’ve been at the forefront of battling the book-banners in McKinney ISD since they began their crusade, over a year ago.) So, yeah. Suggestions?