Can I Still Teach James Baldwin?

Andrew Sullivan has a new post up that highlights an under-discussed problem with the Critical Race Theory panic that’s sweeping America right now.

To Sullivan’s credit, he argues against banning CRT, though that ship has sailed, and those laws are already on the books in several states. Instead of banning, he argues, right-thinking Americans should “expose” CRT, defeat it in the marketplace of ideas. Fine. Whatever. Bring on the exposé. But in the course of his argument, he reveals exactly why bans on CRT (which, whatever Sullivan wants to believe, are the inevitable result of the frenzy he’s helped whip up) are so pernicious to good education — especially to good literary education.

A common retort to the idea that CRT is pervasive in our schools is to point out that Critical Race Theory is not actually taught outside of law school or grad school. Sullivan is having none of that. The teaching of CRT in primary schools, he says, is analogous to the way Catholic theology is taught to children: in pieces, with simple concepts and phrases that introduce ideas that can be elaborated later. “Similarly with CRT,” he writes, “impenetrable academic discourse at the elite level is translated to child-friendly truisms, with the same aim — to change behavior.” We can know this is happening, Sullivan says, by looking for keywords and phrases that indicate CRT is being taught. He writes: “CRT has its own words and values, and they are instilled from the beginning: racism, systems, intersectionality, hegemony, oppression, whiteness, privilege, cisgender, and ‘doing the work,’ as CRT convert Dr. Jill Biden would say.”

There are several problems with Sullivan’s piece, starting with his conflation of CRT with Ibram X. Kendi, and including his misrepresentation of both CRT and Kendi’s work. “No nation, no person, is inherently or permanently racist,” Kendi writes, but you’d never know it from what people on the right say about him. And I haven’t read all of the work of Derrick Bell or Richard Delgado, but I seriously doubt the phrase “do the work” shows up very often in their articles.

But I want to zoom in on that last sentence, where Sullivan lists words he thinks indicate the teaching of Critical Race Theory. Because — wow. That list really makes the stakes clear. Racism, systems, oppression, whiteness, and privilege are CRT’s “own words and values”?

Oh. Well. When you put it that way, I guess I do teach CRT.

Seriously, think of what that means for a literature teacher. Good luck teaching Nella Larsen’s Passing without talking about whiteness or privilege. Good luck teaching Richard Wright or Ralph Ellison without talking about systems of oppression. Good luck teaching Audre Lorde without talking about intersectionality, or trying to teach Toni Morrison, or Zora Neale Hurston, or Langston Hughes, or Gwendolyn Brooks, or Jericho Brown without talking about racism.

If those words belong to CRT, and we’re not allowed to teach CRT, then we’re not allowed to teach those books. Of course those words don’t belong to CRT, but that doesn’t really matter. If they’re going to trigger angry protests at school board meetings and calls for firings, the effect is the same.

…

This is the risk no one’s talking about with these Anti-CRT bills. If enacted and taken seriously, they are going to knock lots of writers of color off of lots of school reading lists. For some anti-CRT pundits, this is a good thing. Those writers don’t belong on the syllabus, they argue, because all those writers do is harp on and on about oppression. Rod Dreher recently skewered the syllabus at a Manhattan prep school that happened to include mostly writers of color. “These daughters of Manhattan elites are being taught to despise their culture before they have been taught to love it. No wonder we’re falling apart,” Dreher said.

What did Dreher hold up as a contrast to this “decadent” syllabus? The reading list at Covenant Classical School in Dallas, where 10th graders only read Shakespeare, Wordsworth, and other British authors. In other words, it’s okay to have an all-white syllabus; the important thing is that students aren’t learning about white privilege.

…

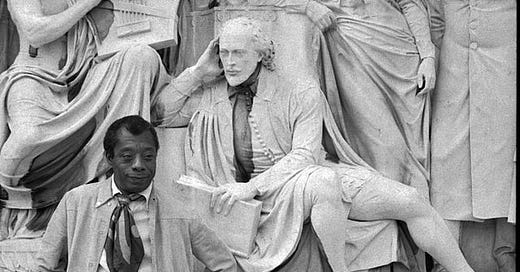

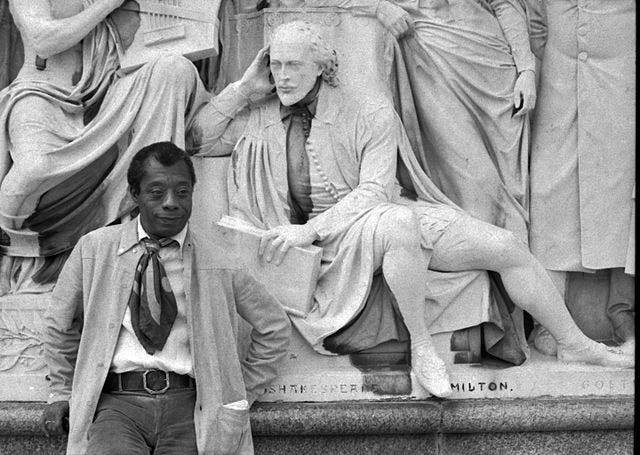

I assign James Baldwin’s “Talk to Teachers” to my 12th-grade AP students during a unit on education; my colleague assigns “Notes of a Native Son” to his 11th-graders as a companion text when they’re reading Richard Wright. I think assigning James Baldwin to high school students is non-negotiable, and I’ve written before about what I think I missed by not encountering his writing until later in life.

Baldwin is *not* a Critical Race Theorist. He delivered his “Talk to Teachers” when Kimberlé Crenshaw was still in preschool. But he is a “critical race theorist” in the sense that Sullivan is using the term and, unfortunately, in the all-encompassing sense that the term has come to hold in public debates. Could reading Baldwin make white students feel bad? I suppose so, especially if certain quotes are taken out of context. Could reading Baldwin contribute to the idea that (in Sullivan’s words) “America is at its core an oppressive racist system”? Absolutely, yes. Does Baldwin talk about racism, and whiteness, and privilege, and systems of oppression? Check, check, check, and check.

Of course, Baldwin rejected both the idea that he was anti-American or anti-white. But so have the real CRT theorists. So has Kendi. That hasn’t stopped them from being vilified.

Also, I don’t teach Baldwin’s essays, or any text, as dogma. I teach my students to read both with and against the grain of any text I assign, and I’m thrilled when students thoughtfully challenge ideas in their assigned readings. In fact, I teach “Talk to Teachers” as a question. Baldwin says:

Now if I were a teacher in this school, or any Negro school, and I was dealing with Negro children, who were in my care only a few hours of every day and would then return to their homes and to the streets, children who have an apprehension of their future which with every hour grows grimmer and darker, I would try to teach them — I would try to make them know — that those streets, those houses, those dangers, those agonies by which they are surrounded, are criminal. I would try to make each child know that these things are the result of a criminal conspiracy to destroy him. I would teach him that if he intends to get to be a man, he must at once decide that his is stronger than this conspiracy and they he must never make his peace with it.

I ask my students, Is that right? Is that really a teacher’s job? And I’ve had students argue intelligently both ways.

But it is true that we don’t question the assertion that racism is structural in the US. After all, the evidence is all around us. I teach in a city where segregation persists and on a campus where, officially, 99% of my students are non-white and 90% of my students qualify for free or reduced lunch. Teaching that racism is systemic is, for me, like a biology teacher teaching evolution is real. I know people deny it, but I can’t do my job and entertain that denialism at the same time.

…

So this is my question: Can I still teach James Baldwin?

I mean it.

If I assign “Talk to Teachers,” are people going to call for my job? Am I going to have grifters like Christopher Rufo going on talk shows, waving around printouts of Baldwin’s quote that America is “a criminal conspiracy to destroy” Black children? Will politicians like Ron DeSantis accuse me of teaching my students to “hate our country and hate each other”?

If I assign the magisterial “Stranger in the Village,” with its biting analysis of white innocence (“American white men still nourish the illusion that there is some means of recovering the European innocence, of returning to a state in which black men do not exist”) am I violating the new provision to Texas law that forbids teaching that might make someone “feel discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress on account of the individual’s race or sex”? Or the one that says I can’t suggest that “an individual, by virtue of the individual’s race or sex, bears responsibility for actions committed in the past by other members of the same race or sex”?

Will Andrew Sullivan protest my class with an image of an innocent-looking white child holding up a sign saying “I am not a monster”?

Again, these are genuine questions. Can I teach Toni Morrison? Can I teach the section of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” on the white moderate? Can I teach Lorde, or Larsen, or Ellison, or Wright, or Brown, or Brooks, or Hansberry, or Baraka? Can I still teach James Baldwin?

And if not, what non-white writers can I teach?