Book banners hate it when you call them book banners.

There are two reasons for this: politically, they know that book bans are unpopular, so being tagged as a book banner can cost them elections and political gains. But the term also wounds them psychically, because to be a book banner is to be un-American, and many book banners want to think of themselves as lovers of freedom.

My normal response is: Tough. I don’t have to play your semantic game.

(I do like the way Lyz Lenz puts it: “A book ban? Didn’t you know? It’s only a book ban if it comes from the Ban region of France. Otherwise, it’s just sparkling content curation.”)

But it is sometimes useful to define disputed terms, and so, with the publication of my Book-Loving Texan’s Guide to the May 2023 School Board Elections, I think it’s worthwhile to spend a few minutes explaining why I choose in the document to refer to the pro-censorship candidates and groups I cover as “book banners.”

Here goes:

The normal argument against the term book banners is that if a book is removed from school libraries, but still available at public libraries or bookstores, it’s not really banned. Here are three reasons why that argument doesn’t hold water.

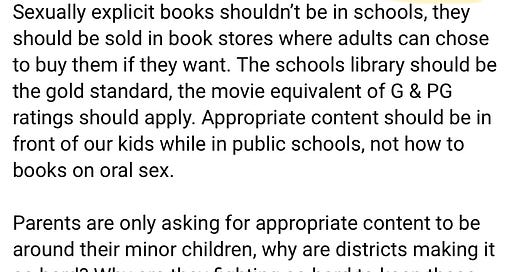

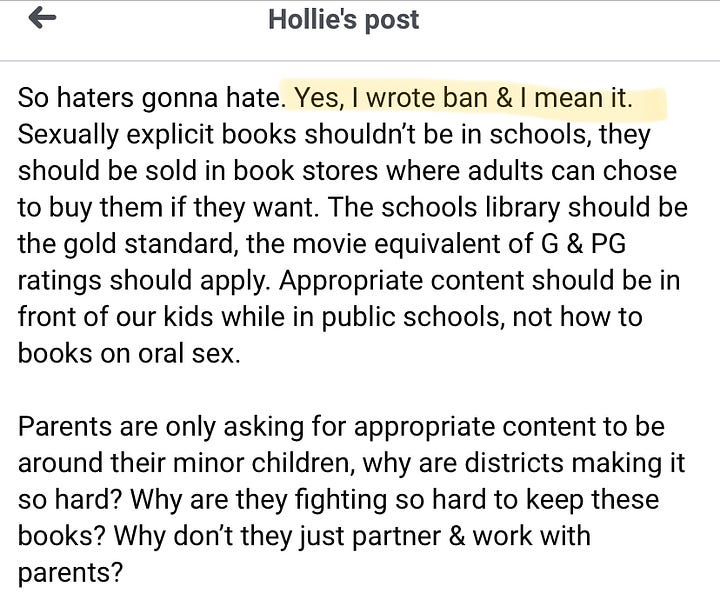

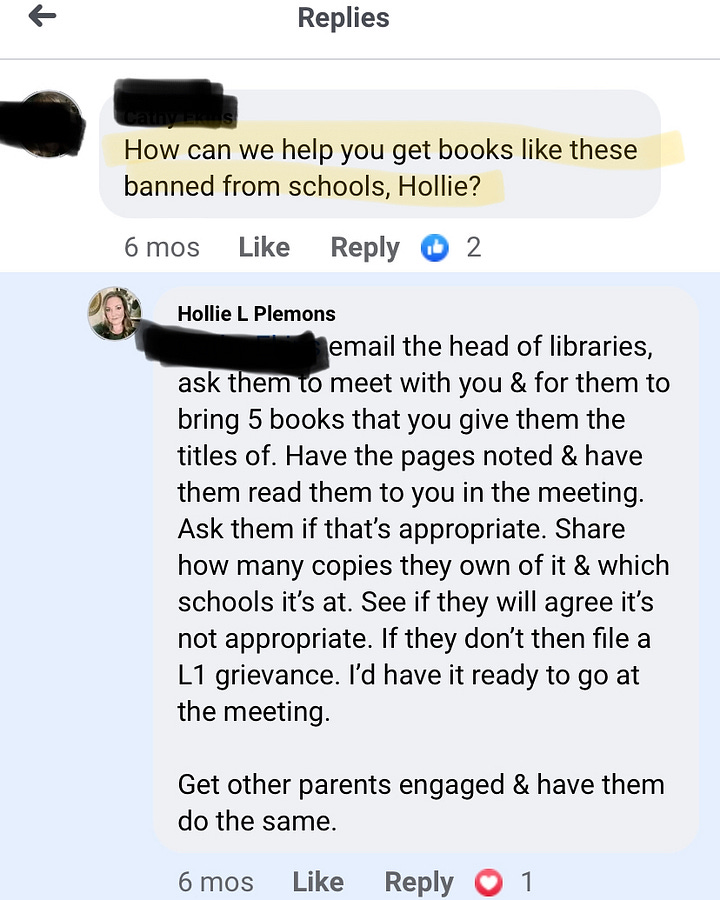

In the first place, to ban something is to officially or legally prohibit it. The groups, individuals, and candidates I cover are all trying to remove certain books from schools and prohibit their re-entry. That’s a ban. Sometimes, they’re trying to prohibit ideas from schools (“gender fluidity,” “CRT”), and that has the effect of eliminating certain books. Also a ban. There’s no way around it; these folks are banning books from schools. And they know this. When they talk among themselves, sometimes they slip and say it. Sometimes they shout it from the rooftops.

So even if they never go beyond removing books from schools, it’s accurate to call them book banners. But, in the second place, the same groups who are trying to ban books from schools are often trying to do the same thing with public libraries and even sometimes bookstores.

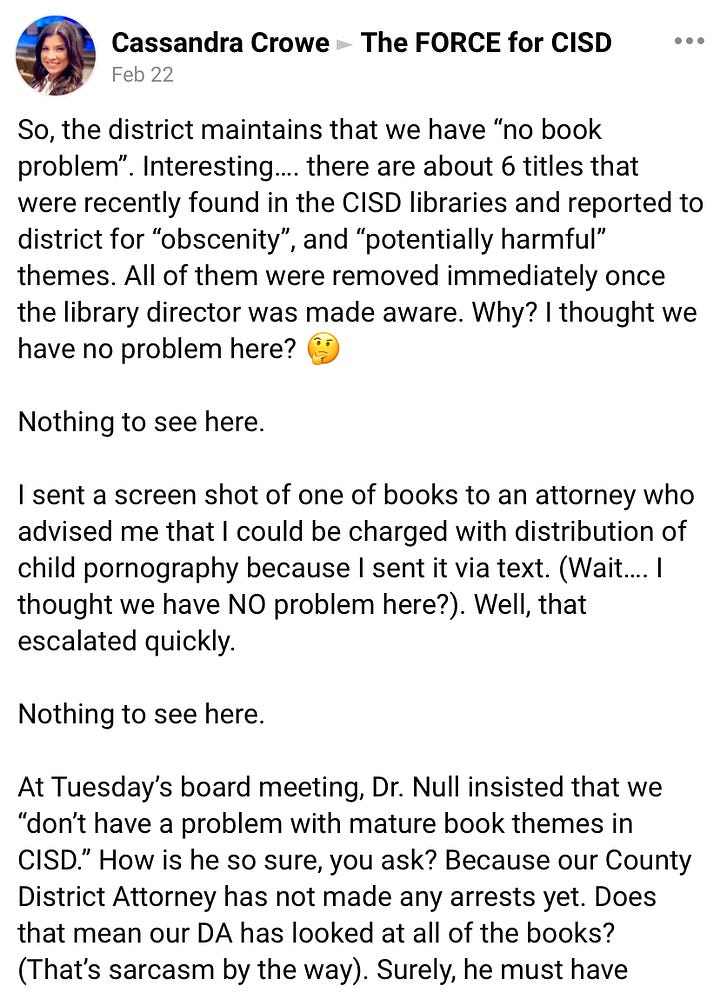

Here, for example, is Texas book banner Cassandra Crowe fighting furiously to get books officially removed from Conroe ISD schools. And here she is also trying to get books removed from the public libraries of Montgomery County.

Actually, book banners’ leap beyond the school library door makes perfect sense, given the logic of their rhetoric. Listen to any contentious school board meeting and you’ll hear All Boys Aren’t Blue or The Bluest Eye or The Perks of Being a Wallflower called “pornographic” or “harmful to minors.” Sometimes they’re described as child porn. You’ll hear the people who make those books available to students called “groomers,” sometimes “pedophiles.” You’ll hear calls to lock up the people who purchased those books for districts.

Then you’ll hear someone go to the same mic at the same meeting and say that they’re not book banners because, if you want your kid to read that book, “You can just go to Barnes & Noble and buy it for them.”

Huh?

Those two positions do not make sense together. You can’t reconcile This book is child porn with Go buy it at Barnes & Noble.

And you can’t square This book is harmful to minors with You should buy it for your own child. Unless you condone child abuse.

In this video made by Humble ISD school board candidate Erin Greene and “Mad Momma Bear” Tracy Shannon, you can watch the incoherence of these two positions dawn on the book banners in real time.

At 16:59, addressing any “groomers” who might be watching, Shannon says, “Groom your own damn kids! Go down to Barnes & Noble, they have a whole bunch of disgusting books there that you can buy for your own personal dirty book collection and you can groom your own kids…”

Then she starts to realize what she’s saying, and she stammers: “but … which …Hopefully we’ll pass laws against that so that … Actually there are laws against that, so hopefully you can eventually be arrested.”

By the end of her rant, Shannon gets it: if you truly believe these books are as bad as she says they are, you have to advocate locking up every bookseller, librarian, and, yes, parent who makes them available to a minor.

And that’s not all! It’s very common, at these school board meetings, to hear certain books described as “obscene,” using language directly, if selectively, taken from the state penal code. That penal code gives a very precise, specific, and well-litigated definition of “obscene,” which is important because, in US law, obscenity falls outside of the protection of the First Amendment. Read that again: obscene material is not protected by the First Amendment. Not for kids; not for adults. So if you say a book is legally “obscene,” you’re not just saying a school shouldn’t provide it to students; you’re saying literally nobody has a right to read it, or buy it, or sell it.

So, yeah, I’m comfortable referring to the folks who are doing everything they can to ban books from schools as “book banners,” because, again:

1) They’re banning books from schools

2) They’re often a part of or aligned with efforts to ban books from other places (libraries and bookstores), and

3) Consciously or not, they’re calling for the removal of First Amendment protections from these books, and the criminalization of anyone who buys, sells, distributes, or possesses them.